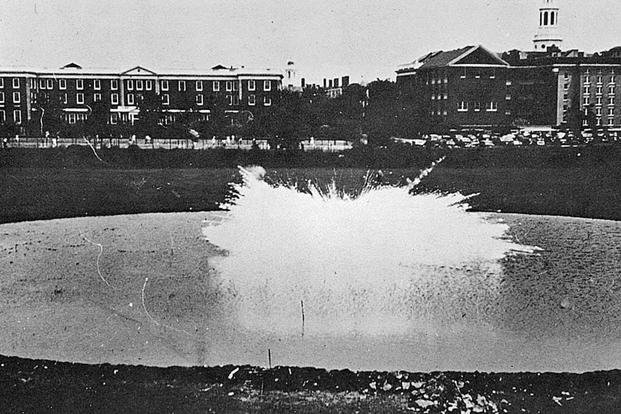

On the morning of July 4, 1942, Harvard researchers and Cambridge, Massachusetts, firefighters cleared the tennis courts on Harvard University's campus. After the white-clad students were led off the field, a nine-inch-deep pool was dug and a device made from "Anonymous Research Project No. 4" was placed.

A Harvard Magazine article recalls that chemistry professor Louis Fieser flipped a switch that activated 45 pounds of the substance, resulting in an explosion that reached 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit. It was a fireworks show unlike anything the world had seen.

It was the first use of napalm.

Although nearly synonymous with the Vietnam War, the first time the world saw a test of this jellied gasoline weapon was during World War II. The United States had entered the war just months earlier and was looking for a way to burn through wooden Japanese cities, as well as create a more effective flamethrower.

Previous attempts at napalm-like substances burned out too quickly. Using regular gasoline to ignite structures proved ineffective in combat, as it would flow away from the target like water. During World War I, the U.S. Army used natural latex to thicken gasoline, which worked better, but not to the extent needed.

When gasoline is thickened using naphthenic acid and palmitic acid (the name napalm is a combination of the terms), it creates a sticky substance that shoots further from flamethrowers and burns slowly and at higher temperatures.

It has the added effect of removing oxygen from the surrounding air faster, causing those in the area to pass out from being unable to breathe and, eventually, burn like everything else around them.

The U.S. Army Air Forces used napalm effectively throughout World War II, both in flamethrowers and in incendiary bombs. It was also used as close-air support ordnance during the Korean War and, of course, Vietnam.

Today's product isn't really napalm, although it retains the name. Now, napalm consists of a mix of polystyrene, gasoline and benzene. The current version is also much safer than the substance used against the Japanese in World War II. It's much more difficult to ignite, requiring the use of a thermite explosion of around 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.