This article by James Clark originally appeared on Task & Purpose, a digital news and culture publication dedicated to military and veterans issues.

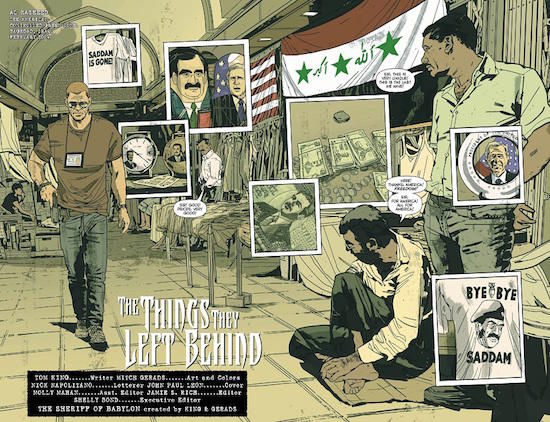

How do you solve a murder in Baghdad in 2004, a place where bodies are discovered daily and violence is one of the few constants? It ain’t easy — and by the time the mystery is solved, many more bodies litter the pages of “Sheriff of Babylon,” a crime drama set during the Iraq War, in comic book form.

Written by Tom King, with artwork by Mitch Gerads, “Sheriff of Babylon” was originally published in December 2016, with the second volume hitting the shelves in February. The series was greeted with immediate acclaim for its uncompromising portrayal of the early years of the Iraq War.

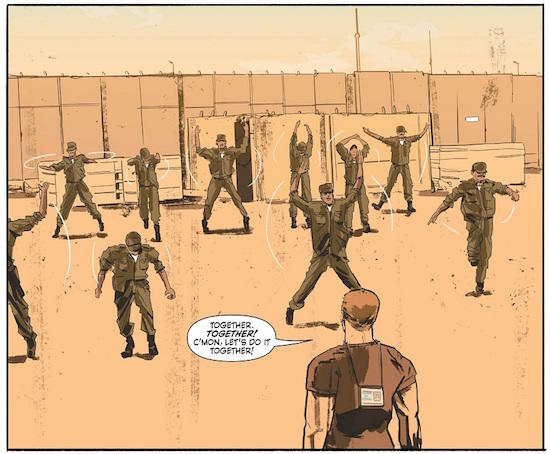

But it’s much more than a story about the war. It takes place almost entirely on rubble-strewn streets, against backdrops riddled with bullet holes and graffiti, at crowded checkpoints, in Green Zone chow halls, hooches, in residential Iraqi neighborhoods, back rooms and vacant buildings. It’s in these places that the seemingly minor details of that war, and that particular time in the war’s life, are cast in sharp relief. “Sheriff of Babylon” shines brightest amid all that grime and grit.

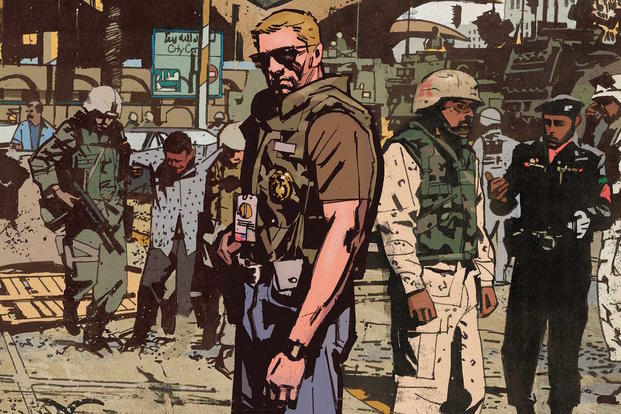

Tom King in Baghdad, Iraq in 2004.

King, a former CIA operations officer who served in Iraq in 2004, worked on the comic with illustrator Mitch Gerads, who also did the artwork for the 2014 run of Marvel’s “The Punisher” series. It’s Gerads’ imagery as much as King’s perspective that brings “Sheriff of Babylon” to life.

“What makes ‘Sheriff’ great, in all honesty, is that it’s drawn very pretty by one of the genius storytellers in the medium, and he’s my partner on this and he’s from a military family and he’s a guy who pays a real tribute to that time in pencil and ink, and it’s mind blowing,” King — who also writes “Batman” for DC and wrote “The Vision” for Marvel — told Task & Purpose. King joined the CIA shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks and served as a counterterrorism operations officer for seven years before leaving to write his first novel, “A Once Crowded Sky.”

T&P spoke with King about depicting something as nebulous as Iraq War counterinsurgency operations in a comic book; his transition from CIA to writing; and what he hopes to see added to the Global War on Terror’s emerging canon of art and literature.

Where did the idea for “Sheriff of Babylon” come from?

From necessity. I didn’t actually want to write about it. I was in the Iraq War a lot less long than a lot of people. I was there for four months in 2004… I didn’t want to go back to that time. I didn’t want to think about it. I didn’t want to engage with it. I’d been approached to write a series and it got rejected. Tried to write another series, and that got rejected.

And I knew this would sell, and at some point you look at your kids and you’re like, it doesn’t matter what I don’t want to write about, I’ve got to write about that thing, you know?

So okay, I’ve got to write about Iraq and I swore I’d never do that, so that kind of puts me in a bit of a hole. So instead of writing a spy series, I wrote a crime series and tried to describe everything I saw, but through a different angle.

How much of your experience has gone into “Sheriff”?

100%, pretty much. I took the tack of not doing any research, which is probably the opposite of what you’re supposed to do when you write something. I wrote it just from memory, I think, every place except for one. There’s one place I made up for plot reasons, and I feel bad about it, but every place but that one was a place I actually visited or a hall I’d walked down. The whole thing… it comes from that.

In terms of a theme, everything I write is based on my war experience or my years in the CIA, you know, fighting against terrorism. It sounds trite, but being involved in that fight, everything comes out of there, it’s who I am.

“Sheriff” doesn’t read like it has an agenda, more like a series of observations, like you’re looking over someone’s shoulder. Was that the intent?

It’s gotten a little better since I started the project, but it seems to me that a lot of people who were writing about the war were writing with a specific agenda. Either on the left or the right and every Iraq thing was either “they lied to us about the WMDs” or “Rah, rah, rah, everything’s great. We fixed everything.”

Neither of those things was my experience when I was over there. It wasn’t about the WMDs, but there was something noble to it, in my experience. A lot of people were trying to build a better world, but there was something tragic about that, because it was a world we were trying to build that wasn’t coming together.

So I wanted to just write about what I observed and not come to it with some kind of agenda. I don’t want to change anyone’s mind about the war or anything I just want to describe what I saw and get you to turn the page to see something else that I saw.

Did you set out to use the characters as stand-ins for the different forces at play in Iraq?

(Laughs.) So I set out knowing I wanted one Sunni, one Shia, and one American. I at least had that thought in my head, just to convey that central conflict. Then I wanted to use some interesting archetypes from when I was there, just as a building block. When you start building a character, you start with a cliche and then you sort of build out to a real person.

I knew a lot of those sort of Shia strongmen who had come from overseas who hadn’t been in Iraq in 25 years, and were coming back to the country, and the experience they were having. I dealt with a lot of those characters. I also met a lot of strong women characters so I wanted to combine those two into one character, who became Sophia. Then Nassir is based on a ton of guys I knew out there who had survived the Saddam regime anyway they could, as honorably as they could, and by trying to survive in an utterly dishonorable system as honorably as you can, inevitably corrupts you. And Christopher (the American contractor) is a combination of a bunch of people.

Christopher is a contractor, and when I was out there it was like 50/50 military and contractors, so if you’re writing about Iraq and you’re not writing about all the guys who have slightly different color badges, but are fighting the same war, seems like you’re missing something.

How’d you go from the CIA to comics?

Yeah, the CIA was the weird part; the writing stuff was always consistent. I wanted to be a writer and interned at Marvel and DC in college, and even sold a story to Marvel, and I was like, “I’m ready, I’m ready to go into the game, ready to write.” And they were like, “The whole industry is collapsing and we’ll be dead in six months,” so I was like, shit I better go become a lawyer.

I worked for the Justice Department… and then 9/11 happened, and like a billion other people, I volunteered for what I could. What I volunteered for was the CIA, and I thought I was going to be one of people who would put the [paperwork] together, but they decided to put me as an operations officer, which are the guys who go out and recruit spies. So I did that for seven years overseas, and then I had a kid.

In all honesty, I couldn’t be the CIA officer I wanted to be and the father I wanted to be. I couldn’t find that balance; some people can, but I couldn’t find it. So I took a year off, wrote a novel at night, took care of my kids and was Mr. Mom by day, sold the novel, and walked away.

You mentioned earlier not wanting to draw on your CIA experience. Is that a hard thing to resist doing because of the wealth of material, or is it an easy decision?

Nah, it’s a real easy decision to not do it. The reason you get to do what you do is because you keep the secrets you keep. Honestly, I don’t want to sound self-aggrandizing, but people’s lives depend on you keeping those secrets — and not just spies in the field, but your friends who are still out there doing the job. It would be a disservice to them. “Sheriff” was the first series where I got a little close to the line; that’s why “Sheriff” was sent to the CIA before it was published — to make sure it wasn’t crossing any lines — and they cleared it. Which makes me feel a little better about the whole thing.

So given your decision to not write about that stuff, do you have any thoughts on how every month it seems like another SEAL comes out with a book that’s ghost-written by someone?

(Laughs.) I don’t feel like I should tell anyone how to make a living. You do what you’ve gotta do. I have problems with the guys who just leak random stuff to Wikileaks, I think that’s crazy. I think they try to hire people who are smart enough to keep the secrets they need to keep; 99% of the time they hire the right people. A lot of the guys writing those memoirs, they know what lines not to cross, that’d be my guess. They know what they’re doing.

Did you have to jump through any hoops to get Sheriff published?

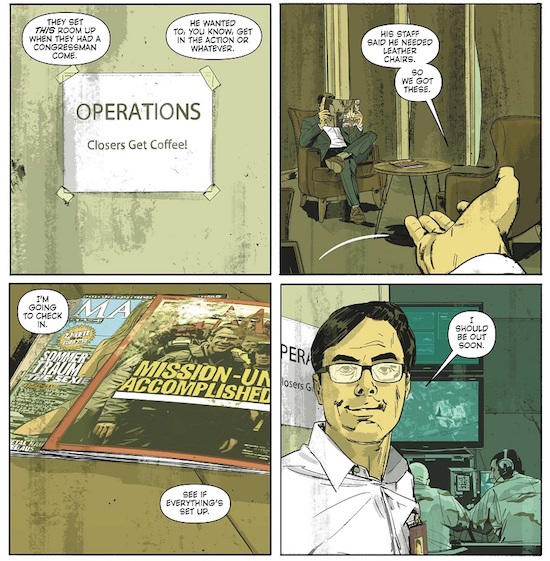

They didn’t make one suggestion, again I know what not to say, so I don’t say it. There’s a great example. At the end of Sheriff there’s an ops room scene and they go into the ops room, and the two characters are left outside. So I put all the drama in the waiting room, because we can’t go inside the ops room because I can’t describe what it looks like. Because if I do, that’s a violation. I can’t say what equipment is being used or what methods and how an actual op would go down, I can’t talk about any of that stuff, but I can talk about the drama going down in the waiting room, we just can’t go past that door.

Did you do that in any other scenes?

There were one or two times where I was like “I can’t describe this to you, because if I do it’ll be a violation, so look in the public and see what you can find and do your best.” I think we did that once or twice.

As more and more people share and talk about their experiences at war in Iraq and Afghanistan, do you have any thoughts on this canon and the direction it’s going in?

It does annoy me that every script I read these days, it’s PTSD. It’s a guy and it’s the most cliche thing: His best friend gets shot and he’s haunted by the experience. But, PTSD is so much more complicated than that, than just one traumatic experience and I’m a little tired of those cliches and it does a disservice by not talking about all the other stuff involved. That what you get from over there, that experience, is a sense of guilt not only for what you did, but what you didn’t do. You miss it in a weird way, you don’t just think it’s horrible, you kind of wish you were there in a weird way, and your memories are formed in a different way. … It’s affecting the whole country and a whole generation of us coming back from this thing, and you can’t just say “we’re doing Vietnam again.” We have our own thing and our own problem. It’s different when a million guys go off to war and 6,000 come back dead, there’s a certain guilt with that, being part of a million survivors.

James Clark is a staff writer for Task & Purpose. He is a former Marine combat correspondent and a veteran of the War in Afghanistan. You can reach him via email at James@taskandpurpose.com. Follow James Clark on Twitter @JamesWClark . This article originally appeared on Task & Purpose. Follow Task & Purpose on Twitter.

More articles from Task & Purpose:

Terminal Lance Creator Says He’s Just Getting Started With ‘White Donkey’