The first astronauts to fly into space in a Boeing Starliner capsule anticipate joining an exclusive cohort of military test pilots.

Since the advent of human spaceflight, U.S. military service members or veterans have flown the inaugural crewed missions for all the nation's spaceflight programs, from Mercury in 1961 through the Space Shuttle era and including SpaceX's Crew Dragon in 2020.

Climbing aboard the Boeing capsule for their forthcoming liftoff -- delayed from the scheduled May 6 launch time because of a problem with an Atlas 5 rocket valve -- are commander Barry E. "Butch" Wilmore and mission pilot Sunita L. "Suni" Williams. Both are retired Navy captains and test pilots. The mission represents each of their third trips to the International Space Station, and the two have flown on different spacecraft each time. As of May 8, the launch was planned for no earlier than May 17.

During his Navy career, Wilmore flew A-7E Corsair IIs and F/A-18 Hornets, including 21 combat missions during Operation Desert Storm. His first time flying in space was a space shuttle mission to the ISS in 2009 for an 11-day stay. He returned to the ISS in a Russian Soyuz capsule in 2014 for a long-duration mission.

Williams flew H-46 Sea Knight helicopters in support of Operations Desert Shield and Provide Comfort and later served in the Rotary Wing Aircraft Test Directorate and as an instructor at Navy Test Pilot School. She first visited the ISS via space shuttle as a member of the space station's first crewed expedition in 2000-2001. She also returned in a Soyuz in 2012, when she commanded ISS Expedition 33.

A two-stage United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket will launch the first Starliner crew from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. Atlas 5s started flying in 2002, and even with the design's track record of 99 successful launches, this Starliner mission will be the first time the rocket type has flown with a crew.

Boeing's Crew Space Transportation-100 Starliner capsule first flew, uncrewed, in 2019, when the capsule failed to reach the ISS. Engineers lost control due to software issues, but eventually regained control and brought the capsule back to Earth. The second uncrewed test flight did make it to the ISS and back, but NASA and Boeing discovered safety issues afterward, including weak parachute cables and tape used in the construction that turned out to be flammable.

Should Starliner successfully complete its voyage to and from the ISS, the mission would mark a major milestone in the history of human spaceflight. Here are the U.S. astronaut crews that, like Wilmore and Williams are poised to do, climbed on top of a rocket to ride on a brand-new U.S. spacecraft for the first time:

Mercury (1961)

Alan B. Shepard Jr.

Project Mercury needed to figure out first things first: Could the United States send a person to space, then bring that person safely home?

The crew: Navy test pilot Alan B. Shepard Jr. answered that question after beating out his six colleagues who made up the remainder of the original seven Mercury astronauts. In the Navy, Shepard had served in a squadron of F2H-3 Banshee fighters and as a test pilot.

The flight: North American Aviation adapted the motor for the single-stage, Chrysler-made Redstone rocket from that of the SM-64 Navaho cruise missile. Meanwhile, McDonnell Aircraft built Shepard's single-seater Mercury capsule. The combination of rocket and capsule had flown twice prior to Shepard's suborbital Mercury-Redstone 3 flight May 5, 1961, once crewless and once with a chimpanzee named Ham inside.

A little more than 2½ minutes after launching from then-Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, the capsule separated from the rocket, and Shepard -- having become the first American human being to experience microgravity -- took the controls. His capsule flew to an altitude of 101.2 nautical miles, or just shy of 116.5 regular miles. A screen showed him his view through a periscope.

"I made this manipulation one axis at a time, switching to pitch, yaw and roll in that order until I had full control of the craft," Shepard recalled, according to NASA. After about five minutes in microgravity, man and capsule reentered Earth's atmosphere and, slowed by parachutes, splashed down in the Atlantic.

Gemini (1965)

Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom and John W. Young

Often described as a "bridge" from Project Mercury to the Apollo moon program, Project Gemini introduced a two-person capsule and, in its first crewed flight, gave astronauts a to-do list of tests to perform and procedures to rehearse "in a complete end-to-end test of the Gemini spacecraft."

The crew: Another of the original Mercury 7 astronauts, Air Force test pilot Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Gemini 3 commander, had flown 100 combat missions in F-86 Sabres during the Korean War. He'd already gone to space as the pilot of Project Mercury's second single-seat suborbital flight, the one after Shepard's. (After Grissom's Mercury capsule splashed down in the ocean, its door had mysteriously blown off, and he'd waited in the waves for a rescue. Later, while practicing for his role as the commander of Apollo 1 in 1967, he and the two other crew members died in a cabin fire on the launch pad.)

John W. Young had flown F-8 Crusaders and F-9 Cougars among other aircraft, including helicopters, in his career as a naval aviator and test pilot. The Gemini 3 pilot would become the first American to operate a computer on a crewed spacecraft during the flight. The computer was for guidance.

The flight: The Martin Co.'s two-stage Titan 2 rocket, derived from the intercontinental ballistic missile of the same name, launched the McDonnell-built Gemini capsule from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, another of the numerous names given to Cape Canaveral over the years.

Perhaps most significantly, the Gemini 3 crew proved that by firing the capsule's thrusters, they could manually maneuver it to entirely different orbits. They orbited Earth three times and, manually once again, piloted the first controlled reentry.

Apollo (1968)

Walter M. "Wally" Schirra, Walter Cunningham and Donn F. Eisele

The Apollo Program's three-seater capsules would eventually fly six crews of U.S. moonwalkers to lunar orbit starting in 1969. But before that could happen, numerous flight tests laid the groundwork in a multitude of configurations of different rocket types, with and without capsules, and with and without crews.

The crew: Yet another member of the original "Mercury 7," Navy pilot Walter M. "Wally" Schirra had flown F-84E Thunderjets on 90 combat missions in the Korean War. By the time of Apollo 7, he'd flown alone on a six-orbit Mercury flight, and he'd commanded Gemini 6 when it docked in space with Gemini 7 to complete the first crewed docking of two maneuverable spacecraft.

Walter Cunningham joined the Marine Corps after Navy flight training because he knew he'd get to fly fighters that way. He'd served in a night fighter squadron during the Korean War and in a later oral history interview said that after 54 missions, he'd never fired a shot. He was a Marine reservist while working for NASA, and Apollo 7 would be his first trip to space.

Also on his first spaceflight was Air Force engineer and experimental test pilot Donn F. Eisele, who'd flown more than 3,600 hours in jets.

The flight: North American Aviation built Apollo's three-seater command modules, while expatriate German engineer Wernher von Braun and his colleagues designed the Saturn 1 rocket, which was modified for later phases of the program. Chrysler built the first stage of Apollo 7's Saturn 1B rocket, and Douglas Aircraft Co. made its second stage. More powerful than a Saturn 1 but still shy of what would be required of the Saturn 5 moon rockets, Saturn 1Bs had previously launched two uncrewed missions.

Taking off from Cape Kennedy, the Apollo 7 crew performed all their maneuvers and equipment tests, and with a "101%" success rate, the astronauts talked NASA into extending their mission to 11 days, ultimately splashing down in the Atlantic.

The astronauts broadcast their activities on live TV for the first time, only possible while within range of ground stations in Texas and Florida that could receive and convert the signals. They ate the United States’ first rehydrated hot food in space and "gave the nation confidence," according to NASA, "to be able to meet President Kennedy's commitment" of a moon landing by the end of the 1960s.

Space Shuttle (1981)

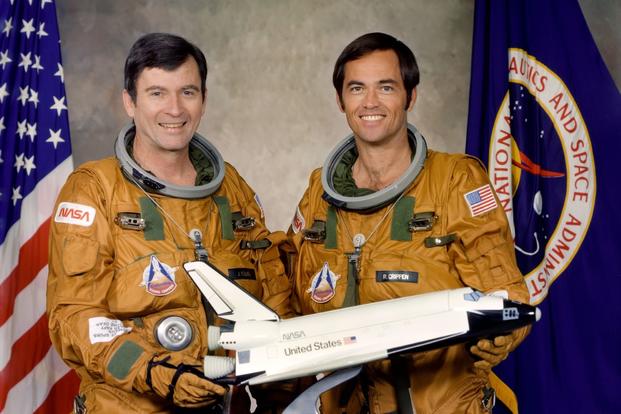

John W. Young and Robert L. Crippen

With the arrival of the space shuttle, military test pilots would finally fly a spacecraft into orbit and then return home to land on a runway instead of in the ocean.

The crew: Navy pilot and Gemini 3 test pilot John W. Young returned for another first crewed test flight, having gone to space three more times in the interim, including the time he walked on the moon as commander of Apollo 16.

Robert L. Crippen had served as a Navy attack pilot in an A-4 Skyhawk squadron and studied, then instructed, at the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School before joining NASA.

The flight: Young and Crippen knew the space shuttle could land. A series of test flights of the prototype space shuttle Enterprise had culminated in five free flights during which Enterprise detached from its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft with a two-person crew and landed.

Ultimately lifted off the planet by NASA's first-ever, solid-propellant boosters, built by a subsidiary of Pratt & Whitney, Rockwell International's space shuttle Columbia orbited Earth for two days. The mission demonstrated that tiles on the outside of the orbiter were subject to loss or damage, a situation mitigated for later flights.

Crew Dragon (2020)

Douglas Hurley and Robert "Bob" Behnken

After nine years of relying on Russia to fly U.S. astronauts to the ISS, Crew Dragon entered the chat, debuting not only the crewed version of the company's cargo capsule but also extending NASA's new commercial-transportation paradigm to human spaceflight.

SpaceX didn't build the capsule and hand it over to NASA: Instead, NASA bought tickets for its astronauts to fly in the privately owned capsule. The same is true for Starliner, as both capsules came about under NASA's Commercial Crew Program.

The crew: An F/A-18 Hornet pilot who became the first Marine to fly Super Hornets, Douglas Hurley commanded the first Crew Dragon crew. It would be his third spaceflight after a space shuttle ISS assembly mission in 2009 and the final space shuttle flight in 2011.

Air Force test pilot and flight test engineer Robert "Bob" Behnken had served on space shuttle missions in 2008 and 2010. He'd worked on developing new weapon systems in his military career and served on the F-22 Combined Test Force.

The flight: SpaceX had plenty of experience flying to the ISS by the time Hurley and Behnken donned their SpaceX flight suits on May 30, 2020; the Dragon design had originated as a cargo capsule to resupply the space station. Crew Dragons launch atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, which also carried its first human passengers that day. The capsule docked with the ISS autonomously and after 62 days returned to splash down in the Gulf of Mexico, officially bringing human spaceflight back to the United States.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.