On Jan. 7, 1973, a man climbed to the roof of downtown New Orleans' Howard Johnson's Motor Lodge. He had already shot the hotel managers and a couple of guests. He then set some of the hotel's rooms on fire before climbing to the roof with a Ruger .44-caliber rifle.

His aim was to attract first responders to the scene so he could kill more of them. In nearby Belle Chasse, Louisiana, just a few miles across the Mississippi River, then-Lt. Col. Charles "Chuck" Pitman Sr. watched it all unfold on TV. Then he did something about it.

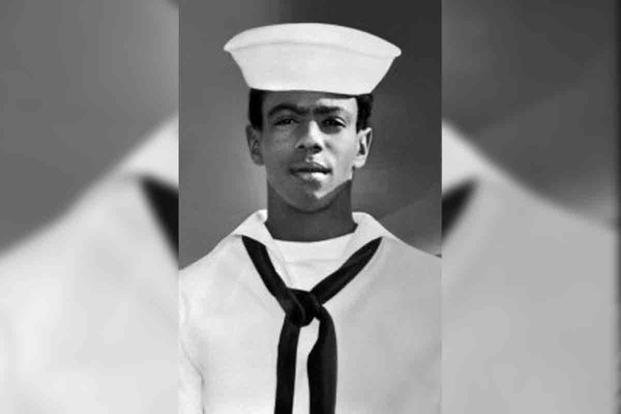

Mark Essex was the man who climbed to the top of the Howard Johnson that January day. Essex was a 23-year-old Black man from Kansas who had enlisted in the Navy as a dental technician in 1969. While serving, he encountered widespread racism in the enlisted ranks unlike he had ever seen in Kansas.

After a physical altercation with a white non-commissioned officer led to increased harassment from his shipmates, Essex went AWOL in 1970 and was declared a deserter. He returned to the Navy one month later, explaining the harassment and intimidation to his superiors.

In February 1971, he was given a general discharge and was living in New York City, where he began to get more involved in the Black nationalist movement. There, he was influenced by some of the movement’s membership, who advocated for armed self-defense against police brutality.

He eventually moved back to Kansas, where he purchased his Ruger .44-caliber rifle and practiced shooting until he became an expert marksman. By November 1972, he had moved to New Orleans. He hadn't told his family he was leaving; he had just packed some belongings and the Ruger rifle and left.

On Nov. 16, 1972, he learned two Black students were shot to death by Baton Rouge police officers during a civil rights demonstration on the campus of Southern University. Essex was enraged at the act of violence and declared war on the police. He wrote an anonymous letter to the New Orleans CBS affiliate, warning he would attack the New Orleans Police Department on New Year’s Eve.

Essex's attack that night killed two police officers and wounded two more. An overnight manhunt for the attacker found only a bloody handprint, but Essex had escaped. Less than a week later, he was driving a hijacked car to the Howard Johnson's, a location he chose because it was across the street from City Hall and the Orleans Parish District Court.

Once inside, he began a spree of violence, killing two hotel guests, the manager and assistant manager and setting fires to several rooms. Within an hour, police and firefighters converged on the hotel. By the time Essex had nearly run out of ammunition, three hours had passed, and police had tried to enter the building numerous times. He killed three more NOPD officers and wounded another 12.

Miles away, then-Lt. Col. Charles Pitman was watching from what is today Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans. Pitman was a decorated Marine aviator who earned a Silver Star, Purple Heart and four Distinguished Flying Crosses flying helicopters in Vietnam. His career was far from over.

After watching the scene for three hours, Pitman acted. As Essex was barricading himself inside the concrete stairwell of the hotel's roof, he commandeered a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter and took three volunteer Marines as a crew.

He flew to a parking lot near the hotel, where he picked up a team of NOPD riflemen and flew past the rooftop repeatedly, attempting to strafe the shooter as he popped out to take shots at the Sea Knight. The siege was then 10 hours old, so Pitman changed his usual tactic of a simple flyby to doubling back after passing the rooftop.

The maneuver caught Essex by surprise, according to NOLA.com, and officers were finally able to get a clear shot at the gunman. Essex's autopsy revealed he'd been shot some 200 times. The New Orleans Police Department considered Pitman's intervention critical in stopping the violence without further loss of life and made Pitman an honorary chief.

The Marine Corps wasn't so happy. It considered Pitman's actions an unauthorized deployment and considered a court-martial for the effort, but Edward Hebert, congressional representative for New Orleans and chair of the House Armed Services Committee, intervened for Pitman.

Charles "Chuck" Pitman went on to be part of the special operations team that attempted to rescue 52 hostages being held at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, in 1980. By the time he retired in 1990, he was Lt. Gen. Charles Pitman. He died of cancer at age 84 in 2020.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.