By October 1944, World War II was looking pretty bleak for the Axis powers, especially in Europe. The Allies had landed in Normandy and were advancing inland in France. In Italy, they captured Rome. The Italian government had fallen, and the Allies were pushing northward past Florence.

Lt. Martin James Monti was desperately flying an unarmed, modified P-38 Lightning photo reconnaissance plane across the Italian Front. Monti was an Army Air Forces pilot, but he wasn't on a recon mission. He had stolen the plane and was headed for the Nazi-occupied city of Milan to defect to the German Army.

Monti was 23 years old when he left his duty station near Karachi, in what is today Pakistan, and made his way to Italy to steal an aircraft. He'd grown up in St. Louis,born into a German and Italian family. When the U.S. entered World War II, Monti and his four brothers joined the military. The brothers had all joined the Navy in 1942. Monti would report for training in the Army Air Forces in 1943.

Before he left for training, however, he made a pit stop in Detroit. It was there he met Father Charles Coughlin. Coughlin was a radio priest whose weekly broadcasts were cut off by the U.S. government in 1939 for their anti-Semitic messages and outspoken support for some of the anti-Bolshevik policies enacted by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Martin James Monti was one of Father Coughlin's millions of listeners, and had grown up tuning into the Catholic priest's fiery speeches. Monti stopped in Detroit to meet with the priest before reporting for duty. It's believed that the two discussed how Monti could support Coughlin's ongoing support for Nazi Germany and work against the Soviet Union, as an airman.

When Monti landed the plane on the Nazi airfield on Oct. 13, 1944, he was captured as a regular prisoner of war, but soon convinced his captors that he was defecting. His plane was seized for intelligence purposes, and Monti "offered his services to assist in the German war effort."

From there, he was sent to Berlin, where he began broadcasting for the Overseas Service of the German State Radio under the name Capt. Martin Wiethaupt, using his mother's maiden name.

He told his American listeners that he was a U.S. Army officer who had deserted the American forces, because they were fighting the wrong enemy. Nazi Germany wasn't America's enemy. He believed the Germans should be an American ally, and that the entire war was a Communist plot to defeat the Soviet Union's Fascist enemies and enslave the whole world. But Monti wasn't much of a radio broadcaster, and before long, Mildred Gillars (also known as "Axis Sally") was back in his time slot.

Monti was then made an officer in the Waffen-SS, where he helped create propaganda leaflets for Allied prisoners of war. This job didn't last long, either. As the Allies closed in on Berlin, he escaped, making his way back to Italy where he could surrender to American forces. He was captured just 48 hours after V-E day.

The Army had no idea Monti had defected to Nazi Germany. They charged him only with desertion and theft of the reconnaissance plane, for which he received a 15-year suspended sentence and was shipped back to the U.S. In 1947, he was readmitted to the Army as a private.

By the time he was ready to leave the military in 1948, the FBI had figured out what happened after Monti stole the P-38. He was rearrested as he was leaving with his discharge papers and charged with 21 counts of treason, which potentially carried a death sentence. He confessed and pleaded guilty.

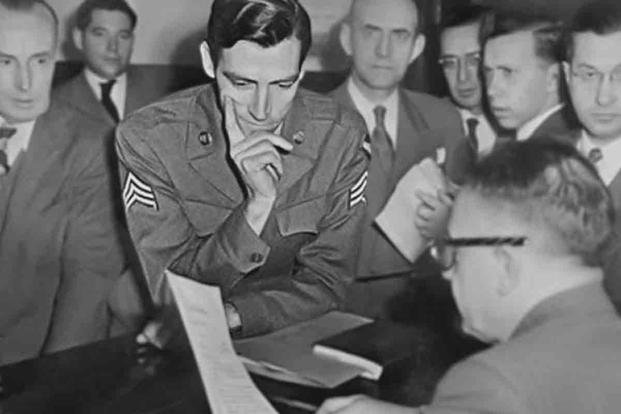

At his 1949 hearing, his defense attorney argued that Monti (now a sergeant) was raised in a vehemently anti-Bolshevik family to believe that Communism was the enemy of the church and the government -- to a "fanatical" degree. Yet, among the millions of listeners of Father Coughlin and the millions who joined the armed forces during World War II, Monti was the only soldier to defect to Nazi Germany.

The judge sentenced Monti to 25 years in prison and a $10,000 fine for his treason. Monti showed no emotion as the sentence was read and went to Fort Leavenworth Prison. He wasn't paroled until 1960, when he tried to have his confession tossed out and sentence reversed. It didn't work. He moved to South Florida, where he died in 2000.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.