U.S. troops have been jumping out of perfectly good airplanes for more than 80 years, but a significant amount of training and preparation has gone into making paratroopers actually combat effective. Arguably, the most important step in those decades of refinement was the first one: Who would be the first to jump from an airplane with only a relatively new technology strapped to their back to keep them alive?

That was U.S. Army Capt. Albert Berry, and he wasn't necessarily jumping out of a perfectly good airplane. The danger didn't start with the jump, and the 33-year-old Berry knew it. No one had survived a jump from a moving, fixed-wing airplane with a parachute -- because no one had ever attempted it.

Still, he climbed aboard a biplane at Missouri's Jefferson Barracks on March 1, 1912, to make history. As he and pilot Anthony Jannus flew over an insane asylum, Berry noted, "That's where we both belong."

Inventors, daredevils and balloonists had been jumping with different parachutes since the 18th century, with mixed success. Many pilots and parachutists jumped to their deaths, confident their chutes would save them, and many more would do the same after Berry's jump.

Parachute technology had come a long way in the lead-up to Berry's leap, but it was far from perfect. American Grant Morton made a jump from a Wright Model B biplane in 1911, but carried the chute in his arms, throwing it open as he jumped. The modern knapsack parachute was created by Russian inventor Gleb Kotelnikov that same year.

The airplane itself was another danger. The 1911 Benoist Type XII School Plane that Berry and Jannus were flying was a pusher-type aircraft, with the engine and propeller in the rear of the plane. This meant the danger of striking the propeller after exiting the aircraft was real, and would not only mean Berry's untimely demise, but also the loss of the aircraft and its pilot.

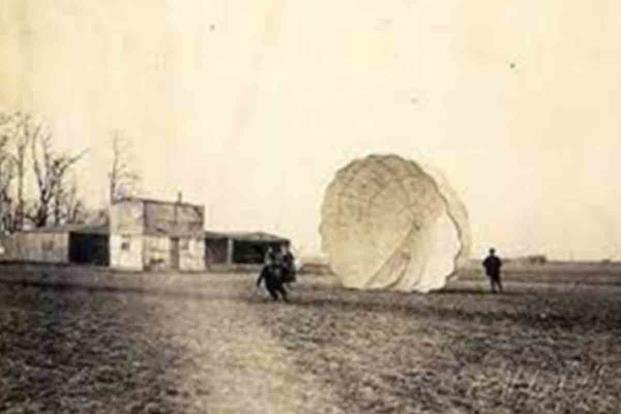

Berry, however, was a skilled parachutist. He'd made a number of jumps from hot air balloons since the age of 16 and felt confident about this jump. Rather than use a knapsack parachute, Berry's chute was stored in a cone-shaped container below the plane's fuselage and was attached to a harness on his back so that it would billow open as he fell away from the aircraft. All his choices were deliberate, meant to ensure a successfully soft landing.

On the afternoon of March 1, 1912, Berry and Jannus took off from Kinloch Field near Jefferson Barracks, circling the airfield for some time to test the air currents and the quality of the engines before making their climb to 2,000 feet. Jannus then piloted the aircraft over the nearby Mississippi River and pulled into a turn to make the final pass over the barracks. Berry climbed down the biplane's landing gear and sat on a kind of trapeze bar at the front of the plane. He then hooked the parachute to his harness and cut loose.

Nowadays, the Army's minimum acceptable altitude for a parachute jump is 400 feet above the terrain at an airspeed of at least 150 knots. When Berry jumped, the plane was only traveling 55 mph, or around 47 knots. Berry also told The New York Times that his initial freefall drop was 500 feet, so although the airspeed was much lower than what is considered safe today, Berry was fortunate Jannus was at a much higher altitude.

"Had it been my first drop in a parachute, I would have lost my nerve and probably my life," Berry said. "I descended so rapidly, I began to feel uneasy about whether the parachute would open."

At the time, Berry claimed he would never make such a jump again, saying he was unprepared for the "violent sensation" he felt when he cut away from the biplane. But like many a first-time skydiver, he would do it at least one more time, on March 10, 1912.

It would be almost 30 years before the U.S. Army created its first parachute infantry platoon in 1940. By that time, the battlefield effectiveness of paratroopers was already proven in combat as Nazi Germany dropped men called Fallschirmjäger into Norway and Denmark. After the Germans suffered massive Fallschirmjäger casualties in their invasion of Crete in 1941, they abandoned the idea of paratroopers, but the Allies didn't.

The Allied forces of World War II would perfect combat parachute jumps, as they dropped 20,000 troops into occupied France on June 6, 1944. Another 41,000 British, American and Polish paratroopers would drop into Holland during Operation Market Garden later that same year. The combat effectiveness of dropping soldiers behind enemy lines meant the U.S. Army would continue paratrooper operations into Korea, Vietnam, Panama, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.