As a Seabee, Roy Aaron Ford helped get soldiers and equipment onto the beaches of Normandy. Ford tells the story of the Rhino barges made especially for the beaches of Normandy. From his experience in country from June 6 through September 15, Ford provides readers a personal glimpse into the food, lifestyles and experience of the Normandy invasion.

My name is Roy Aaron Ford.

I served with the 111th Naval Construction Battalion, otherwise known as the Seabees.

I entered the service as an apprentice seaman. When I was mustered out a little more than two years, eight months later; I had achieved the rank of signalman, third class. I entered the Seabees in Denver, Colo., June 15, 1943 and was mustered out on Feb. 27, 1946 at Camp Shoemaker, California.

My first assignment was boot camp in July 1943 at Camp Perry near Williamsburg, Va. Around the first of August 1943, our battalion was transferred to Camp Endicott, at Davisville, R.I.

Journey to England

On January 30, 1944, our unit boarded the British ocean liner, the Mauritania, in New York harbor, and after eight days of rough seas and constant seasickness, we arrived in Liverpool, England. On arrival in England, my company, Company B, was sent to Falmouth, in Cornwall.

The first night in Falmouth resulted in a rather humorous introduction into the war. Falmouth, England was a town about a mile square. Scattered throughout the town were large blimp-like balloons tethered by steel cables. Every night, in addition to a total blackout, these balloons were released several hundred feet into the air. There were also several large machine gun emplacements and search lights located throughout the town. Near the town was a long railroad bridge which every night would attract at least one German aircraft.

On our arrival, we were quartered in some steel barracks called butler buildings. Sometime after midnight a German plane came over, the searchlights went on, and the machine guns started firing. If that racket weren’t enough, we heard loud explosions on the top of the barracks. Sure that we had been bombed, we all scrambled out of the barracks like a bunch of rats in varying degrees of undress only to learn that some of the bullets from the machine guns had come down on the buildings. So much for our introduction to the war.

At Falmouth, I went to signal school and learned both semaphore and Morse code by light. Morse code by sound would have involved the use of radio, which would have enabled the enemy to hear our communications.

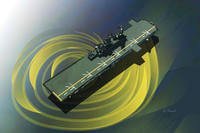

Shortly after our arrival at Falmouth, the 111th Battalion was designated a pontoon battalion. We were to build the Rhino ferries and tugs, man them and then participate in the invasion of France. Our company built the barges in Plymouth, England. Each Rhino was built of large steel cubes, approximately 6 feet on a side.

They were bolted together in strings of six pontoons wide and thirty long.

They were powered by two large outboard Chrysler marine motors with a top speed of two to three miles an hour. When fully loaded they drew only about two feet of water.

Each Rhino was accompanied by a tug, which was three pontoons wide and six long. It also had two large inboard motors to aid in the maneuvering of the clumsy Rhinos.

A Rhino could completely unload the military vehicles on one LST (Landing Ship Tank). The LST was an excellent ship for transporting military vehicles.

It was very effective in unloading vehicles and supplies in the beaches of volcanic islands of the South Pacific.

But, would have been very ineffective on the beach at Omaha because if it were to have unloaded at Omaha Beach, it would have had to wait to the next high tide, until the ship could pull off the beach.

Since their draft [the Rhino's] was so shallow, they had no difficulty getting off a shallow beach and underway once they were unloaded. Each Rhino and its tug were assigned to an LST, which was to tow them across the English Channel. We departed from Portland, England on the morning of June 5. The weather was terrible, cold, cloudy, windy and raining. The tugs had a pontoon tube mounted on the front with a hole cut in the sides so the crews could get some protection from the weather, but it was still a miserable, seasick-y trip.

Ashore at Normandy

We departed from Portland, England on the morning of June 5. The weather was terrible, cold, cloudy, windy and raining. The tugs had a pontoon tube mounted on the front with a hole cut in the sides so the crews could get some protection from the weather, but it was still a miserable, seasick-y trip.

We arrived at the rendezvous area about fifteen miles off the coast of Normandy at about 3 a.m. on the morning of June 6. There were four or five big battleships lined up about a mile apart. It was very dark but each time one of the battleships fired a salvo, the sky would light up everything as far as the eye could see. We managed to “marry” our Rhino to the LST and began unloading by about 5 o’clock. It was just getting light. After three or four hours, we cast off and headed toward the shore. I was a signalman and deckhand on the tug.

Because of the intense enemy gunfire throughout most of the day, our Rhino was not able to beach until late in the evening when it was just getting dark. As we arrived on the beach, we could see human bodies floating around in the shallow water like logs. It was very disgusting.

While we were unloading, a small plane flew across the beach dropping bombs. I don’t think it caused any great damage, but it did cause some excitement. Finally, around 10 o’clock, we pulled the Rhino off the beach and headed out to sea. After we got about a mile out, we dropped the anchor, and crawled into the pontoon because we were exhausted.

Around 7 o’clock the following morning, our chief woke us up chanting -- they are shooting at us. Sure enough, you could see little "plinks" in the water nearby. Instead of pulling up the anchor by hand, someone got an axe and chopped the chain in two and let it go to the bottom. We promptly got further out to sea. We spent the rest of the day tied up to a liberty ship that was unloading military vehicles and supplies by crane with large cargo nets and ferrying them to shore.

For the first three or four days, we slept on a troop ship and if it was near mealtime when we were unloading a cargo ship, we ate with them. They always had excellent food, as did the troop ship. Anything was better than the k-rations we survived at first. The whole invasion process was so stressful; I doubt that any of us ate anything on the first day.

After the bluff above the beach had been secured, a camp area was established and a mess tent set up which served hot c-rations. Heat didn’t improve the flavor but the hot food was much appreciated. Each of us had been given a half of a pup tent back at boot camp, and a fellow by the name of Howard Larsen from Oregon became my roommate. He was about five and a half feet tall and I am six foot four so we were referred to as "Mutt and Jeff." We dug a “foxhole” about six and a half feet long and four feet wide and about 18 inches deep. Then we pulled all the grass we could find for a mattress and it became very comfortable for sleeping and shelter when the wind blew.

Peaches and Fruit Cocktail

One day, as we were coming off duty, we discovered a barge with canned goods in cases -- six gallons each. I stole a case of fruit cocktail and Howard got a case of peaches.

And we supplemented our hot c-rations with delicious canned fruit and shared them with a number of our neighbors and we were very popular for a couple of weeks afterwards. We would be on duty for 24 hours unloading ships and then off for 24 hours.

In August, a regular tent camp was established and we slept on folding cots. The food improved markedly also. While in this camp, I had one day off and was able to visit the small town of Caen in Normandy. It was an interesting experience; they had a beautiful cathedral. This was my first opportunity to see public urinals out in the middle of the street. They were set up and situated so that you could see men’s feet and legs and their heads, of course, which was kind of unusual. There was very little to eat in the town although they had raised a lot of potatoes, and you could get what they called potato sandwiches. I guess the sandwiches were nourishing, not terribly tasty but you could survive on it. They also made something they called coffee, which somebody said was made out of poached barley. It tasted much like Postum that I remember having as a child. It was an interesting trip; I would love to go back sometime.

On September 15, our battalion was relieved by the 69th Construction Battalion and we returned to Plymouth, England. We soon returned to Camp Endicott in Rhode Island, where we were given leave and I observed both Thanksgiving and Christmas of 1944 at home. I reported back to the base on New Year’s Eve 1944.

Just as an addendum, we soon got on a troop ship in Boston and sailed through the Panama Canal to the Philippines by way of Hawaii and Wake Island. We established a new camp on a small island at the southern tip of Samar. From there, we participated in the invasion of Borneo.

On our return to the Philippines, we learned that the 111th Naval Construction Battalion had been decommissioned. I was then assigned to Guam where I guarded Japanese soldiers building a cemetery.

I was honorably discharged from the service in the rank of signalman, second class.

[Editor's Note: The recording for this transcript was created May 18, 1999, and is provided to Military.com by The Eisenhower Center for American Studies, University of New Orleans.]