World War I has been noted for the amount of incredibly evocative war poetry it produced, notably from such soldier-poets as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. However, very few of those well-known poets were American. Joyce Kilmer, who went to war with the New York National Guard’s famed 165th Infantry Regiment, the “Fighting 69th,” was a renowned American poet before he was killed at the Second Battle of the Marne in 1918.

In 1917, Ralph Moan of East Machias, Maine, was working as a civil engineer for the town of Waterville. On April 6 of that year, the United States declared war on Germany. Exactly three weeks later, Moan gave up his job to enlist as a private in Company K, 2d Regiment of Infantry, Maine National Guard. Moan may have had many reasons for choosing to enlist in the National Guard in a time of war: adventure, travel, and a chance to be part of something greater than himself. Following several months of guard duty in Maine, Moan and the rest of his unit left for Westfield, Massachusetts. There, the regiment was redesignated the 103d Infantry Regiment and became a part of the 26th “Yankee” Division, so named as all of its units were from New England. To bring the 103d to full strength of 3,500 men, soldiers from New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island National Guard units were brought into the regiment. With barely enough time to incorporate the new men into the regiment, the 103d was on its way “over there.”

On 9 October 1917, Private Moan and the rest of the 103rd Infantry arrived in Liverpool, England. From there they entrained for Southampton, where they went into rest barracks. At this time, thousands of doughboys were flooding into England to become part of the massive Allied war machine. This was a new and fascinating experience for the boys from rural Maine, most of whom had never left their own state, let alone country. Moan and his buddy Foster Tuell went exploring, expressing great fascination with British money and British women. Their efforts to “see what the English girls were like” ended in disappointment after the objects of their affections stood them up. Undaunted, the young men—Moan was but twenty years old—continued to explore their environs until 16 October, when they boarded a ship to Le Havre, France.

When they arrived at Le Havre, the 26th Division became the first full American division to arrive in France, as well as the first National Guard division. From Le Havre, the 103d Infantry moved into winter quarters around the town of Neufchateau. There, the young men endured a harsh winter where they often had to pawn their belongings to buy food and, as some of the first Americans there, had to construct their own barracks, all while undergoing a rigorous training regimen from French instructors.

Moan’s own diary from this time period expresses his own youthful optimism, being more concerned in finding “a good feed,” dancing (he writes with great frustration over being denied dances with Red Cross women because that was the purview of officers), or singing with his friends than in the goings-on of the war. In January, he was assigned the position of mechanic in the company, responsible for maintaining trucks, weapons, and equipment. The promotion came with a pay increase, but it also meant that during combat he would serve as a litter-bearer or runner.

At the urging of their division commander, Major General Clarence Edwards, the 26th Division was sent to the front ahead of schedule. In a series of foot marches and rail trips, the division arrived on the Chemin Des Dames Front near the French city of Soissons in early February 1918. Moan wrote of seeing the ruins of the towns and scavenging for war artifacts. In successive marches, the 103d Infantry moved closer to the front lines, witnessing the effects of the war firsthand. However, Moan’s war seemed mild and carefree in the early months of 1918, as he and his friend Tuell sat outside in the French sunshine watching Allied and German airplanes dogfight in the clouds. Most men had never seen an airplane before and were continuously amazed to watch the biplanes that darted through the air. Since the men were so new to war, they did not yet know enough to get under cover when they heard an aircraft overhead, but would instead rush outside to get a look. At night they watched the long searchlight beams pick out German aircraft and then remarked in amazement at the streams of antiaircraft fire that were sent skyward. This was a quiet sector of the front, and the 26th Division was still learning the tactics of trench warfare under the tutelage of their French teachers.

As part of this period of instruction at the Chemin des Dames, platoons, companies, and then battalions were all rotated to the front lines. At the time, infantry regiments were composed of three battalions of four companies each. The AEF adopted the model of their hosts, with one battalion on the front lines, one in support a mile back, and the last battalion in reserve. This allowed for a defense in depth. The 103d Infantry held forward positions along a canal, with their support troops billeted in old limestone quarries out of sight of searching enemy aircraft.

The French and Germans had held an informal truce had held on the Chemin des Dames before the Americans had arrived. Both sides were severely worn from fighting and this sector was a place where battle-scarred units could come to rest and regroup. The Yankees changed that, firing at anything that moved and “turning no-man’s land into Yankee land,” as one division history noted. One sniper in the 103d Infantry was averaging one German a day.

For the men in the support and reserve positions, the war was only seen when enemy aircraft flew over, or when the rare shell whistled in and exploded in a flurry of dirt. On 15 February, the regiment took its first battle casualty when Private Ralph Spaulding of Madison, Maine, was killed by an enemy shell. Private Moan, in support near the limestone quarries, noted that shelling intensified when their work parties got closer to the front lines. The ground that they held had been the scene of fierce fighting the year before, and blasted trees, bombed out houses, and the detritus of war met the men’s eyes wherever they looked. In all of this, Moan and his fellows maintained an optimistic outlook as only young men can.

Everything changed for Moan and his fellow soldiers in March. On 6 March, the 3d Battalion, 103rd Infantry, of which Moan’s Company K was a part, took over responsibility for the first line of trenches, directly opposite the German lines. Moan moved into a dugout, a small dwelling containing a light one-pounder gun and covered with logs for protection against enemy fire. It was here that Moan’s carefree attitude vanished. The morning arriving at the front, Moan was rudely awakened from sleep when a German shell struck his dugout during an artillery barrage. He wrote that he could count at least seventy shells striking per minute, stating, “The man who said he was not scared is a liar.” The Germans hit the Yankee lines with a mixture of high explosive and poison gas shells. Massive explosions rocked the 103d Infantry’s positions for two days as the men huddled down in the trenches wearing their gas masks. Over the next few days, Moan hauled casualties over barbed wire entanglements and through muddy sloughs. His job as a litter-bearer meant recovering casualties under fire and then hauling them back to the battalion aid stations, sometimes more than a mile.

Since a canal ran between the German and American lines in the 103d Infantry’s position, the doughboys did little in the way of patrolling and were rarely raided by the enemy. However, a German patrol tried to probe part of Company K’s line on the night of 11 March. The watchful Yankees spotted them and hit the enemy with grenades, rifle fire, and machine-gun fire from behind the protection of a railroad embankment. The next morning, the doughboys could see the bodies of twenty dead German soldiers ensnared in the barbed wire along the company’s front. “One [German] man had his head blown off and it made a ghastly sight, suspended in the barbed wire,” wrote Moan the next day. Company K was relieved on 12 March and returned to a second line trench, but this brief stint on the front had soured Moan’s view on life. On 30 March, he recorded his last journal entry, one that captures in fierce anger the plight of combat veterans of all wars: “Have decided to cut this diary out right now, for no man wishes after seeing what we have seen to recall them but rather wishes to forget. From now on, all we see is HELL.”

One might think that after this damning indictment of combat, Ralph T. Moan might have vanished from the history books. In reality, it was just the beginning. On 5 July, the 103d Infantry Regiment entered the blood-soaked boughs of Belleau Wood to relieve the exhausted U.S. marines and soldiers of the 2d Division. Enduring nearly two weeks of enemy artillery fire, gas, and probing attacks, the 26th Division finally struck back in the opening moves of the Aisne-Marne offensive. Company K, with the rest of 3d Battalion, went over the top for the first time in the early morning hours of 18 July, seizing the small village of Torcy. In a week of severe combat, the 26th Division advanced fifteen kilometers before being relieved by the 42d Division. After three weeks in a rest area, the 26th reentered the fray at St. Mihiel on 12 September.

After the summer campaigns, the Allies began planning for the final operations to break the German lines and, potentially, bring an end of the war. This culminated with the Meuse-Argonne offensive, where, on the morning of 26 September 1918, thirty-seven French and U.S. divisions advanced against German positions along the Meuse Rover and in the Argonne Forest.

To create a diversion from the main assault, two battalions of infantry from the 26th Division were detailed to make a raid on the towns of Riaville and Marcheville on the plain of the Woëvre River to tie down German forces and prevent them from reinforcing other positions along their lines. The 1st Battalion, 103d Infantry, was to move on Riaville, while 1st Battalion, 102d Infantry (Connecticut National Guard) would target Marcheville. Ralph Moan’s 3d Battalion was on outpost duty on the main line of the American-held trenches, overlooking the plain of the Woëvre. The 1st Battalion, 103d Infantry, advanced through the fog on the morning of 26 September against only light resistance until they entered the town of Riaville. Here, the Yankees encountered concrete machine-gun positions and snipers, supported by artillery. The doughboys entered the town, were pushed back, counter-attacked, and were pushed back again. German minenwerfer fire began to fall on the beleaguered American infantry and casualties rose. Major James W. Hanson, commanding the battalion, sent back reports that his liaison with his own supporting artillery was failing and that he could not get sustained artillery fire on German positions.

During the Meuse-Argonne campaign, Moan served as a runner. This was an important duty, as the first thing the enemy targeted during a firefight was the lines of communication, such as field telephone lines. The Riaville Raid was no different. The wires for field telephones were cut almost immediately by artillery fire and runners were taking heavy casualties as they braved the shell-riddled open plains back to the American lines. The smoke and heavy fog that lingered over the town made artillery observation difficult, so Moan had to make several trips back and forth between the lines, a distance of 250-300 yards, to relay messages to the supporting batteries. His third trip was necessitated by friendly artillery firing short, their rounds impacting in front of the town where 1st Battalion was hunkered down in an attempt to gain a foothold. Moan took off once again, trying to avoid the German artillery barrage and timing his run to follow it down the field. His luck, however, ran out and he was tossed twenty feet by an exploding shell. He awoke later in a hospital, after the raid was over; concussed but alive. The plucky doughboys of the 103d Infantry had fought it out in Riaville all day. During the course f the day’s fighting, the town exchanging hands several times. Once darkness fell, they withdrew, accomplishing their mission of a diversionary raid, at the cost of ten killed and fifty-three wounded.

For Ralph Moan, the war was over. He was sent to recuperate in Grenoble in the French Alps. After the Armistice on 11 November 1918, he rejoined his regiment and his buddies, who, despite wounds, had survived the war. To help fill the time in the weeks and months following the Armistice, Moan and three fellow soldiers formed a singing quartet to entertain the troops. He returned home to Maine in 1919 as a corporal to find that he had been awarded both the French Croix de Guerre and the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery on 26 September 1918. His citation read:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, 9 July 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Mechanic Ralph T. Moan, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company K, 103d Infantry Regiment, 26th Division, A.E.F., near Riaville, France, 26 September 1918. Mechanic Moan, who was detailed as a runner, made several trips carrying important messages across terrain swept by constant fire from machine-guns, snipers, trench mortars, and artillery. His disregard for personal safety and devotion to duty in the prompt delivery of messages contributed greatly to the success of the action. (War Department, General Orders No. 21, 1919)

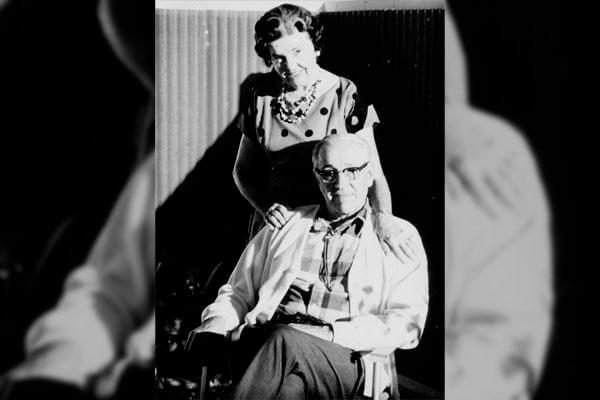

From here, Moan receded into history, becoming one of the millions of World War I veterans across the United States. After the war, he followed his love of singing and performing as part of vaudeville shows and on Broadway. The horrors of war did nothing to extinguish his love of life as “Ralph Moan, Famous Baritone” provided amusement to audiences all across the country. Oddly enough, Moan’s path would lead back to the U.S. military. When he and his second wife, Kathreen, ended up working at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in 1957, she as an Army artist and he as an Air Force administrator. Ralph’s creative process did not end with singing; he won first place in an Armed Forces Writers League short story contest and was a member of the Tucson branch of the Arizona State Poetry Society. In fact, he seems to have pushed his war memories far behind him, never speaking about them with his children or grandchildren. He was a lifelong member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Disabled American Veterans, and the Freemasons.

And there in the recesses of history he might have remained, but for the diligent work of Kathreen. In 1982, the year of Ralph’s death, she provided the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center with Ralph’s diary, as well as the following poem that he wrote at an unknown date after the war. In it, Ralph depicts the events of 26 September 1918 and shows that despite outward appearances, the war was far from over in his mind:

“So this then was the culmination:

To die—

Die in the stinking mud.

Twice before I’d crossed this no-man’s land,

Darting from shell hole to shell hole.

I’m no hero—

I was numb with fear.

But this time a barrage was on.

I lay there at the waste land’s edge—

Thinking.

Was there any way?

To the right lay crack shot snipers,

To the left in the brush,

Machine guns,

Hungry – waiting.

And fair in front great bursting mud clouds

Playing toss

With bodies.

“Get through once more, son,”

The colonel had said.

“Communications down, our guns firing short,

Killing our boys.”

Yes, it must be done, but how?

Wait!

The barrage, sweeping across the field and back,

A deadly windshield wiper –

Were I to follow it down

And when it returned

Dig in – I might –

NOW!

Drunk with fighting fear,

I chased the mud cloud down the field

Kicking dead bodies,

Twisting like a ghost,

And I laughed, and I yelled,

“You bastards! You can’t get me!”

Our trenches ahead,

Almost there!

Back came Hell’s windshield wiper

Vomiting death and I dug in—

Dug in with all I had.

Mom—dear God help me!

On it came. Forty feet—

Twenty feet—

God!

My head—torn from my body!

________________________

Is this what being dead is like,

Peace, quiet, clean white sheets?

My head must still be here,

It hurts me.

These must be my fingers

I can move them.

And now a voice,

“My boy. For you

The war is over.”

You hear that, Mom?

I’m still alive, I did not die.

I’M COMING HOME!”

Presented in stark and vivid detail, Moan captured the essence of the brutality of war as clearly as Owen or Sassoon. In his poetry, we can see the emotional scars that he carried with him forever as a veteran of some of the most horrific fighting of the twentieth century. Like so many combat veterans, Moan found solace in putting pen to paper and writing. These few lines of verse must surely place Ralph Moan of East Machias, Maine, as one of the soldier-poets of World War I.