In the wake of reports that a Navy psychologist played an active role in convicting for drug use a sailor who had reached out for mental health assistance, the service is standing by its policy, which does not provide patients with confidentiality and could mean that seeking help has consequences for service members.

The case highlights a set of military regulations that, in vaguely defined circumstances, requires doctors to inform commanding officers of certain medical details, including drug tests, even if those tests are conducted for legitimate medical reasons necessary for adequate care. Allowing punishment when service members are looking for help could act as a deterrent in a community where mental health is still a taboo topic among many, despite recent leadership attempts to more openly discuss getting assistance.

On April 11, Military.com reported the story of a sailor and his wife who alleged that the sailor's command, the destroyer USS Farragut, was retaliating against him for seeking mental health help.

Jatzael Alvarado Perez went to a military hospital to get help for his mental health struggles. As part of his treatment, he was given a drug test that came back positive for cannabinoids -- the family of drugs associated with marijuana. Perez denies having used any substances, but the test resulted in a referral to the ship's chief corpsman.

Perez's wife, Carli Alvarado, shared documents with Military.com that were evidence in the sailor's subsequent nonjudicial punishment, showing that the Farragut found out about the results because the psychologist emailed the ship's medical staff directly, according to a copy of the email.

"I'm not sure if you've been tracking, but OS2 Alvarado Perez popped positive for cannabis while inpatient," read the email, written to the ship's medical chief. Navy policy prohibits punishment for a positive drug test when administered as part of regular medical care.

The email goes on to describe efforts by the psychologist to assist in obtaining a second test -- one that could be used to punish Perez.

"We are working to get him a command directed urinalysis through [our command] today," it added.

Later, the same psychologist is listed on Perez's nonjudicial punishment paperwork as a witness. Although Perez was told he had tested positive when a second test was conducted, he was never provided with paperwork of a positive test, according to his wife. After she demanded the document be produced, Perez's punishment was overturned, she said.

Military.com is not naming the psychologist, a Navy officer, because it does not appear that they violated Navy policy or been charged with any wrongdoing. However, the documentation provided by Alvarado strongly suggests that the medical provider who was responsible for treating Perez was also actively participating in his legal proceedings.

Sean Timmons, a managing partner at the law firm Tully Rinckey and a former Army judge advocate general officer, told Military.com that "it sounds like the psychologist has participated in a conspiracy to set him up."

Timmons explained that the military has a policy known as "limited use" that is supposed to protect some drug test results from being used against service members.

"If you have an alcohol problem or drug problem and you go see emergency room care ... if you test positive after a self-referral, that's not supposed to be used in an adverse manner against you," he explained.

"It sounds like they immediately gave another test, then they used that second test," Timmons said, referring to the second test mentioned in the Navy doctor's email. "That's corrupt -- that's not legally sufficient."

The Navy, through Angela Steadman, a spokeswoman for the service's Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, agreed that "while reportable to the command for awareness, medically ordered drug testing and alcohol marker testing cannot be used for administrative proceedings by the command."

Steadman said the reasoning behind that prohibition is not patient confidentiality but "chain of custody" issues.

She was responding to overall policy questions posed by Military.com and not speaking specifically on Perez's case. Traditionally, none of the military branches will address allegations in which an individual's medical records or private information are involved, given privacy concerns and regulations.

Steadman went on to say that "the command can do a command urinalysis or breathalyzer, or both, upon the Sailor's or Marine's return" from treatment.

Dr. Stephen Xenakis, a psychiatrist and retired Army brigadier general, said the doctor's behavior struck him as unethical.

"I can see no justification, when it comes to doing good care -- good medical, clinical care -- for this psychologist to disclose this to the commander," Xenakis told Military.com in an interview.

"I think it violates the basic principles of what we need to do," he added.

Steadman says that, overall, "positive drug tests ordered by mental health and other medical providers are reported to the Sailor or Marine's Commander if they meet the command reporting requirements" in a Department of Defense instruction.

That instruction lists nine reasons for which a health care provider needs to break confidentiality on either mental health or substance abuse conditions. Some are self-explanatory, such as "harm to self" or "harm to others." But other reasons are far broader and open to interpretation, like "harm to mission;" an "acute medical condition" interfering with the "ability to perform assigned duties;" or "other special circumstances in which proper execution of the military mission outweighs the interests served by avoiding notification."

Timmons said that the "significant number of loopholes" is intentional and that they are used so regularly that "the limited use policy is functionally worthless."

"If they want to retain, they focus on limited use. If they want to toss the sailor, they focus on the loopholes and accomplish the objective through gamesmanship," he said.

Steadman was asked by Military.com why the service doesn't provide sailors with a clear right to confidentiality with their medical providers, like civilians, and whether Navy leadership is concerned that the weak protections for mental health treatment will deter service members from seeking help.

She did not reply by the time this story was published.

Incidents like the one Perez faced are problematic, considering the reputation and trust issues the military already faces in getting help for its service members.

"You've undermined the effectiveness of any mental health services and broad services that you need, particularly at a time when you're seeing more suicides and all sorts of other problems within the active duty and the family," Xenakis said.

Senior leaders, like Adm. Mike Gilday, the Navy's top officer, have recently released a number of messages about mental health meant to counteract the stigma associated with seeking help. In last year's message for Mental Health Month, Gilday, told "all of our leaders out there, no matter your rank" to "talk to your people, listen to them, be available, and encourage them to seek help if they need it."

Studies have shown that it is common for some service members to turn to drugs and alcohol -- especially marijuana -- as a way of self-medicating and coping when suffering from mental health ailments. For example, Marine Cpl. Tyson Manker, who was dismissed with an other-than-honorable discharge after he was caught using marijuana, told The New York Times the drug helped him deal with the traumatic experiences he encountered in Iraq in 2003.

Manker sued the Navy and forced the service to review thousands of general and other-than-honorable discharges awarded to troops over the past decade for problems that may have stemmed from a military-related mental health condition or sexual assault.

If the comments from service members on social media on mental health stories are any indication, the message isn't getting through. Stories about retaliation against sailors like Perez are consistently met with cynical quips over the lack of surprise at the news or a plethora of anecdotes involving specific instances of unsupportive leaders.

Xenakis, who in civilian life has focused some of his efforts on using technology to improve health care services and sustain military readiness, thinks that decades of war have taken a toll on the entire military.

"The whole chain of command, up and down, has been just beat up over 20 years ... and everybody's struggling," he said. "Some of the senior leaders that have survived and gotten through it just detached themselves from it."

Timmons, whose practice involves routinely defending military clients, also points to the inconsistent and often confusing system of regulation surrounding drugs in the military as part of the problem, and the fact that false positives for cannabinoids happen in particular.

"The military is a large bureaucracy, [with] a lot of moving parts and a lot of overlapping regulatory guidance," he said. "[Commanders] don't look at the deeper guidance."

However, the lawyer is quick to note that "part of this is because robotically they check the box and move on."

On a form designed to let Perez's leadership make recommendations for how his case was to be handled by the ship's commander, his division officer simply wrote "Zero Tolerance Policy," while the department head wrote "NSTR. Cut and dry case." NSTR is often an acronym for "Nothing significant to report." All four leaders recommended he be punished with a nonjudicial proceeding.

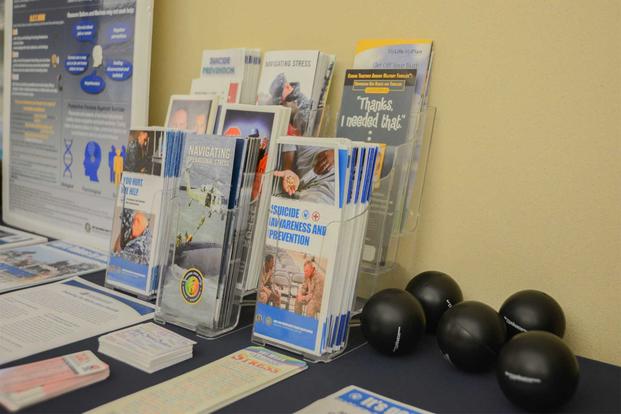

While stories like Perez's paint a grim picture for service members looking to get assistance for mental health struggles in the military, help is out there.

Outside organizations like Stack Up, Military Helpline or the Veterans Crisis Line offer crisis response and limited counseling options with the promise of confidentiality. The first two are not affiliated with any government organization, while the last is run by the Department of Veterans Affairs, not the military.

Military OneSource, which is run by the Department of Defense, is also an option. However, its website notes that "present or future illegal activity" falls outside of its confidentiality promises.

Xenakis explained that service members looking for help don't necessarily need to look for a professional. "There are people out there that you can trust, and you have to use your personal instincts to go find that individual," he said.

"It's not about the treatment, it's about the therapist," he added.

"I always tell everybody, nothing is more valuable than your life," Timmons said, adding that "you can always clean the records up later, if necessary.

"Yes, the military may very well act in an unprofessional manner or have a very draconian, vindictive response, but nothing's more valuable than your long-term future," he explained.

The lawyer also encourages sailors who are facing legal issues not to hesitate to get legal advice "as a minimum, through the free services available on installation from the uniformed attorneys."

If you or someone you know needs help, the Veterans Crisis Hotline is staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at 800-273-8255, press 1. Services also are available online at www.veteranscrisisline.net or by text, 838255.

-- Konstantin Toropin can be reached at konstantin.toropin@military.com. Follow him on Twitter @ktoropin.

Related: A Sailor With Diagnosed Mental Health Issues Says He's Being Targeted for Seeking Help