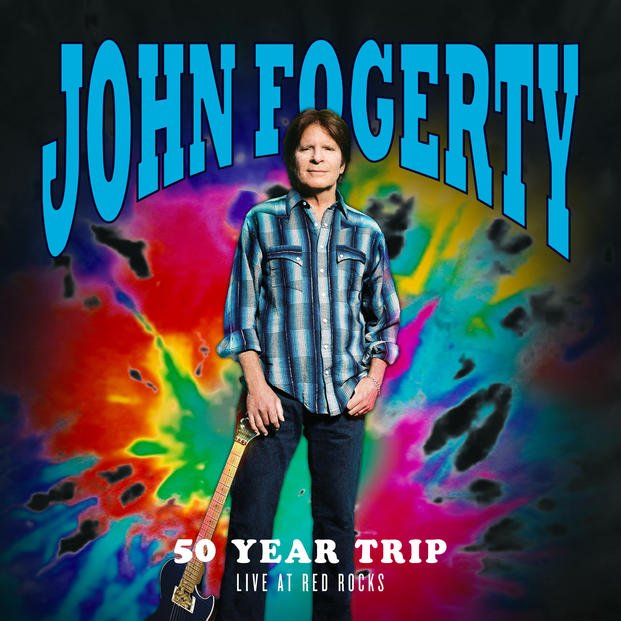

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member and Army veteran John Fogerty is celebrating his half-century music career with a new CD and digital release of "50 Year Trip -- Live at Red Rocks" and a special Veterans Day showing of the concert film in theaters around the country.

The concert includes John's hit songs from his time in Creedence Clearwater Revival and his own solo albums. Fans can find out where to see the film by visiting the Fathom Events website.

John, who's currently playing a run of shows in Sin City, will also dedicate the "Proud Mary John Fogerty Container Home" at Veterans Village in Las Vegas on Monday, Nov. 11. The organization uses repurposed ocean shipping containers to provide affordable housing for individuals and families in need.

John spoke to us about his work with Veterans Village, his own military career and his work with veterans support groups. We also talked about how he wrote "Fortunate Son," his new "50 Year Trip" release and got the scoop on this year's 50th anniversary release of Creedence Clearwater Revival's scorching live set at the 1969 Woodstock Festival.

Military.com: Can you tell us about your work with Veterans Village?

John Fogerty: There's a man in Las Vegas named Arnold Stalk. He has a facility called Veterans Village that he built a couple of years ago on a converted motel property. It's one of those projects where you get everything all ready to go ahead of time. Then, once you break ground, they had a little ceremony that I attended. They break ground and then, boom, they build that thing like in 30 days.

They expanded their facility to have a warehouse and offices. More recently, he started converting shipping containers. So it's big iron or metal boxes that you see going across the ocean on a ship. Arnold converts those into living quarters. It's a really neat thing that ends up costing far less than it would to make a new house.

I've been supporting that effort. We've built one so far that [my wife] Julia and I are calling Proud Mary, and we will dedicate it and give it to the veteran who has been selected by Arnold on Veterans Day.

I didn't start out in life to be a special charity guy or a do-gooder or anything. I just had certain feelings, especially having gone through the Vietnam era and watching the inadequate way our veterans were treated. Over time, I realized that this was something that was close to my heart. It was something I wanted to do something about.

So I contributed here and there and played at benefits and stuff like that. You get going on something like this, and it becomes easier and easier. You're trying to talk other people into seeing how easy this is. It's a cause that needs a lot of work, and here's a way you can help.

Military.com: Can you tell us about your own military service?

JF: I was in the service during the Vietnam era. It was a very volatile time in America. The war was very unpopular with young people. And I have to admit, I was one of those young people protesting the war. I would do it again if there's another one like that.

As a very young person, I was right in the crosshairs, you might say, and I eventually got my draft notice, just like so many other folks. It actually says, just like in the movies, "Greetings from the President of the United States." I managed to get into an Army Reserve unit after receiving my draft notice and served my time.

Of course, there were other things I wanted to do, but we all have a duty and, if it's our time, then that's what we've got to do. I went through that like millions of other guys and then sadly watched the poor treatment of our veterans coming home, particularly from the Vietnam War.

That really upset me. I knew how all those guys felt because I've at least been drafted and was in the military even though I didn't go to the jungle. Most of the people, I dare say, they could've chosen something else. They wanted to do far more than be in a jungle in Vietnam.

It just seemed like we shamefully turned our backs on veterans. And that's when I started to get my hackles up, I guess. I said, "Now wait a minute." After my own service, when the war was still going, I would talk to other young people who were protesting and say, "You're looking at that soldier over there. Don't you realize he's 19? He's just like you. He likes the same stuff. He likes the music; he likes your clothes. He likes the radio station and the movies and TV shows. He's just like you. It's just that he got drafted and so we asked him to do that or else we'll put him in jail."

If you're going to protest, then protest to the people who are waging the war, not the people that are having to fight the war. I still feel that way. So it gave me a different perspective than some of my non-military friends.

Military.com: That's a perspective I hear in your song "Fortunate Son." That one gives me chills every single time I hear it.

JF: There were things I had read about when I was a young person, even in grammar school. We heard about the unofficial class system that even America has. During the civil war, you could pay your way out of your draft or you could actually find a substitute. I used to read that in the sixth grade and I go, "Oh, how does that work? Hey, where you been? You know, go fight in the war instead of me."

When I became 18, I had to go down and register with selective service. This war was going on in Vietnam, and it was such a high profile in our media and part of our culture. It was urgent to me because I have to figure out what I have to do.

If you gave me a choice, I don't really want to go to Vietnam. I had a sense that there were folks who were rich enough or powerful enough to keep their kids out of that situation. Having been in and out of the military by the time I was 22, the concept that you could avoid service because of who you knew really pissed me off.

I'm sure other guys who were just like me and grew up as normal American citizens never dreamed that one day they would be asked to go off and fight in a war you didn't even believe in.

And then somewhere within yourself, you muster up the courage and the sense of country and duty that says, "Well, OK, I guess I gotta do this. I don't want it to do this, but I guess I got to do this." Certainly by the time you get mustered out, if you survive, you are proud of your service because you did what was asked of you.

So to see that there are other people who just have connections or money or both and can avoid it even though they shouldn't be able to, that's something that would really make a normal person angry. And of course they'd be angry.

At first, it was just my personal beliefs. And then one day I realized, "I think I'm writing a song about this," and I went into my bedroom with a little tablet and a pencil. I really didn't know the form of the song or that, you know, that "It ain't me" part or any of that. It just sort of landed on me in a very quick rush. Literally in 20 minutes, I walked into the room and walked back out of the room with a song, which is by far the fastest that that ever happened. In the end, it was a like a whirlwind.

Military.com: Where did you get the idea for "My 50 Year Trip"?

JF: My wife Julie is very creative at putting things together and got this idea for a 50-year anniversary of my career because things really started taking off in 1969. So it seemed like a neat idea to make a show that's reflective of those things. The title of this show is "My 50 Year Trip," which, you know, it's descriptive enough that you get a sense of what it's going to be about. Even though you may not know anything else about me or the music, it sorta gives you at least some kind of direction.

We worked the show out through performing it during my Vegas run back in April or May earlier this year. We decided we wanted to film the thing. Julie thought that this was worthy of being captured in a visual way. Red Rocks is a wonderful venue up in Colorado. That's just such a beautiful, mystical place to be presenting any kind of a show, and it turned out to be the perfect spot for this.

We chose a wonderful cinematic director named Jeff Richter to do the filming. I don't know much about that world at all. But Jeff turned out to be an amazing choice because he did such a great job with the filming and with having all the right camera angles and of course he edited the film and got it into the form that you see now.

I'm very lucky, very blessed that this came together this way. Luckily, there were folks smarter than myself, especially my wife, who are able to choose the right folks to work with us. I'm just very impressed with the whole thing.

Military.com: This year, you finally released your live set from the Woodstock Festival CD and LP. Why did it take 50 years for you to decide to let us hear that complete show?

JF: Back at the original Woodstock, Creedence followed the Grateful Dead, and the Grateful Dead was, uh, how can I say it? They were true to form. They were taking LSD as they walked on stage at Woodstock and therefore very quickly became non-present. And so their set wasn't very good. There was a period of an hour where they were silent, and we thought it was our turn to go onstage. But no, no, they're still up there. Lord knows what they were doing.

Then, the Dead started playing again. You know, it was the middle of the night and the crowd had been rained on, they were hungry. Many of them didn't have clean clothes or the right clothes. They just went to sleep because the Grateful Dead was boring them to tears. So that's what I was presented with when it was Creedence's turn to go on stage. We came out rocking and rolling. We were young guys with a new band and new music and very hungry and ready to show the world what we could do. After two or three songs of people not responding, we started wondering, "Well, what's wrong?"

At some point, I actually go up to the mic and say something like, "Well, we're playing our hearts out for you. We just want you to enjoy it." Well, little did I know they were asleep; that's really what was going on. By the end of our set, they were all awake. Creedence did a great job of warming up an audience for Janice Joplin, but our performance, at least audience-wise, was a bit of a project. I just thought that that wasn't something I wanted to show the rest of the world on film.

The filmmakers sent me "Bad Moon Rising," and they said we want to use this in the movie.

We were good. It sounded like the record and it was well done, but it was nothing exceptional. And I knew the other parts of the set were really exceptional, but they weren't asking for that. Those were kind of longer songs. I think they didn't want to give us that much time.

So I just said no. I didn't think I wanted to show the world that we are in front of an audience and having trouble keeping their interest. The real truth, of course, was they had been put to sleep by the Grateful Dead.

We were doing quite well everywhere else, so I just really never looked back. As it turned out, because the Beatles broke up, we ended up becoming the number one band in the world shortly after Woodstock. Obviously, my not being in the movie didn't really hurt us too bad.

I have always thought it would be great if this thing could be seen in total some day because I know we did a really good set, a very strong set. We didn't phone it in, by any means. We were young and hungry and ready to challenge the world with our music.