They were some of the first Marines to push into Iraq, and now their unit has lost more members to suicide than it did in the war's most ruthless battle.

Thirty-five members of 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, have died by suicide since 2003. That surpasses the number of Marines the unit lost during the Second Battle of Fallujah, serving as a stark reminder of the wounds still carried by many who fought the war's toughest fights.

Operation Phantom Fury, the second chapter of the fight to retake Fallujah from Iraqi insurgents, will forever be known to Marines. It was the service's bloodiest urban combat since the Vietnam War's Hue City, and incredible examples of combat heroism and famous images of brotherhood emerged from the fight.

But 3/1, along with other Marine and Army units who fought in Phantom Fury, faced significant loss. Fallujah has left its mark on every service member who patrolled its streets, according to those who fought there. They're forever linked by gritty combat and heroism -- as well as terrible memories and loss.

And that loss has continued to build in the 15 years since the start of the fight.

"We've lost more guys to suicide than we lost in the battle now," Jake Edwards, a former combat engineer who fought as a lance corporal in Fallujah. He left the Marine Corps as a sergeant in 2009.

Now a crisis trainer for a Virginia school district, Edwards has been on a mission to bring Phantom Fury vets back together. They need to continue honoring those who didn't make it home, he said, and for those who did, they need to keep their support networks strong.

"There's so much that lives with us 15 years later," he said. "If you don't come together and gather, and then healing is limited -- especially with those you bled with."

Edwards has spent months raising money and finding sponsors for a Phantom Fury reunion. He didn't want Fallujah vets to have to spend a bunch of cash to be involved, so he got donations and help from the Semper Fi Fund, Azalea Charities, Reunite the Fight and others. The venue, food, beer and shuttle busses to and from a nearby hotel are covered.

More than 250 Marines and soldiers are expected to attend the Nov. 8 event, exactly 15 years after Marines set out to launch the assault. Attendees will range from four-star generals who led the battle to junior enlisted troops who cleared rooms.

"You never, ever forget the people that you fought with," said retired Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Carlton Kent, who served as I Marine Expeditionary Force's top-enlisted leader during the battle. "I think that that's the most important thing. It's going to be therapy for those warriors to see those people after all those years."

'Stay in Touch with Those Marines'

Jeremiah Workman was awarded the Navy Cross for his heroism in Operation Phantom Fury. He also tried to take his own life after the battle.

Like many who fought in Fallujah, Workman struggled, he said. Fifteen years later, not a day goes by that he doesn't think of the Marines they lost, he said.

"I've done lots of therapy, I've done the medication, the counseling," he said. "The suicide rates are extremely high right now. They have been for a long time. And I think it's just important to be able to lean on your family ... and stay in touch with those Marines."

All these years later, Kent is one of the Marines with whom Workman stays in touch. Their relationship, which Workman refers to as like that of a father and son, dates back to a conversation they had on a road in Fallujah.

A corporal at the time, Workman led his team into the house where Marines were pinned down by insurgents.

The situation was indicative of the challenge troops faced in Fallujah, where enemy fighters -- with caches of weapons -- hid among civilians. Marines like Workman often had to get danger-close to the enemy when called on to clear rooms.

Workman is credited with repeatedly sprinting up a set of stairs while facing a barrage of small arms fire and grenades to help save Marines. Inside and outside the house, Workman's "heroic actions contributed to the elimination of 24 insurgents," his citation states.

Two 21-year-olds, Cpl. Raleigh Smith and Lance Cpl. James Phillips, were killed inside the house. A third Marine, Lance Cpl. Eric Hillenburg, also 21, was killed by sniper fire on his way to help clear the house.

When Workman and his Marines made it out, they were devastated, Kent said.

"I just told them to stay focused, you know, that I saw that everybody's hurting because they were," the former top-enlisted Marine said. "They were down, but I said, 'We've got an enemy that's desperate right now. So we've got to stay in the fight.'"

The situation had taken its toll though. Workman detailed his struggles in his book, "Shadow of the Sword: A Marine's Journey of War, Heroism, and Redemption." The Navy Cross recipient recalled drinking heavily and suffering nightmares about that stairway he kept running up in that house.

Eventually, he wrote, he tried to take his own life. His family found him in time to stop it.

When Kent became the sergeant major of the Marine Corps, he brought Workman onto his staff. He trained with him, helped him focus and said he always told Marines it was OK to ask for help.

"If [Workman] could do it, you can, too," Kent said. "You've got to have trust in other Marines. Asking for help is not a sign of weakness."

'The Darkness' Took Over

Edwards had his own struggles after Fallujah.

During the height of the fight, he was too anxious to eat. As a combat engineer, he was responsible for helping the grunts breach barriers. He also served as a squad automatic weapon gunner.

Edwards didn't leave with 3/1. Instead, he got attached to another infantry battalion and stayed in the city for months.

Some of that was rewarding, he said. They were helping to rebuild Fallujah after so much devastation, and they got to see the first attempt at an Iraqi election in 2005.

But he also had a lot of time to think about what he'd seen there. The details were so vivid, he said. His plans to make a lateral career move and become a human intelligence Marine began to fade. He started giving up on his career.

"I let the darkness and the fears in my life take over," Edwards, who eventually transferred to the Reserve, said. "I had a period of, like, a year or two when I just had zero cares about anything in the world."

Like Workman, Edwards leaned on his family. His parents and siblings helped, he said, but he began making real progress when his uncle, who'd seen combat in Vietnam, began talking about his own experiences. The two also rode their motorcycles through the mountains.

That type of safe haven is what Edwards hopes to provide in next month's reunion. Post-Phantom Fury suicides have hit all the ranks, from enlisted to officer, he said. No one is immune to the stresses of combat.

The event will give Marines and other Fallujah veterans a chance to share what's on their minds or ask questions of leadership about what happened there, he said.

Former Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Casey, who served as commanding general of Multi-National Force-Iraq during the battle will give remarks. Retired Lt. Gen. John Sattler and Kent, who led I Marine Expeditionary Force in Iraq from 2004 to 2005, will also speak.

Retired Lt. Gen. Richard Natonski, who as a two-star led 1st Marine Division and the ground-maneuver element in Fallujah, will provide a declassified battle brief. Retired Col. Mike Shupp and Sgt. Maj. Eduardo Leardo III, who led Regimental Combat Team-1, will also address the crowd.

Phantom Fury veterans have until Saturday, Oct. 19, to register for the reunion.

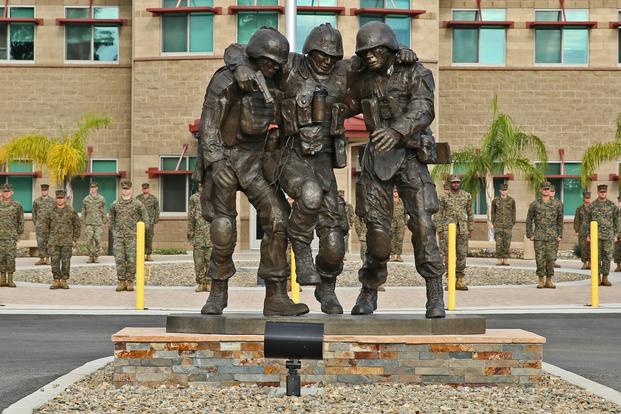

About 500 Fallujah veterans gathered at Camp Pendleton in 2014 to commemorate the battle's 10th reunion. That event was clouded by the Islamic State group's stronghold on the city Marines fought so hard to keep out of the hands of terrorists. That kicked off a yearslong effort to combat ISIS, which ended when the Iraqis retook the city in 2016.

Former Commandant Gen. Robert Neller started a reunion website in 2017 in an effort to address suicides.

"I ask all Marines to get connected. Find your fellow Marines," he wrote when announcing the website. "Reach out, catch up, and when needed, help others."

Workman said the reunion will be cathartic even if Fallujah never comes up. Whether they talk about football or what they've been up to since leaving the Marine Corps, he said it's just important to just be in the same room, honoring their fallen comrades and reminding each other they're there to help.

"My plan is to go and meet as many people as I can, since there's going to be several units there, including Army units that were on the ground," Workman said. "If they want to ask for ideas about how to get over the hump or how to get out of a rut in life, I'm more than happy to help anybody while I'm there.

"But I think just getting together is going to be powerful for a lot of people."

Editor's Note: If you or someone you know needs help, the Veterans Crisis Line is staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at 800-273-8255, press 1. Services also are available online at https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/ or by text, 838255.

-- Gina Harkins can be reached at gina.harkins@military.com. Follow her on Twitter @ginaaharkins.