Valerie Nessel doesn't believe her husband, Tech. Sgt. John Chapman, was left behind in Afghanistan to fight or die alone.

His mother, Terry Chapman, believes he would have wanted his fellow U.S. special operator teammates to get out of the line of fire as fast as they could, even if it sealed his own fate.

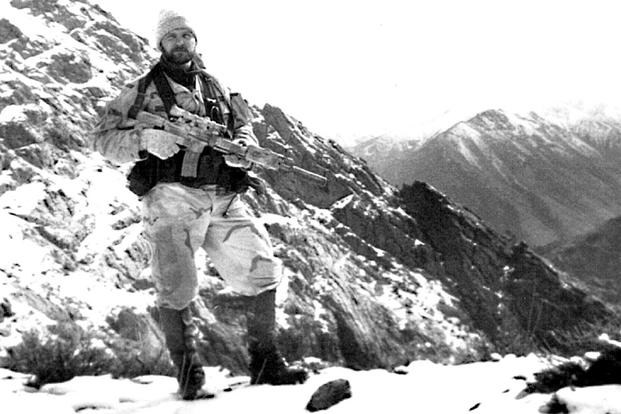

It was the right choice not just for Chapman, but for all the Americans fighting that day on the Takur Ghar mountaintop in southeastern Afghanistan's Shah-i-Kot Valley to press on and stay safe, the two women said.

"Each of those men were doing what they were trained to do at a 10,000-foot [battleground] in waist-deep snow. You can't quarterback ... anything [there]," Nessel said Tuesday. "Each of those men are heroes. They were being shot at from each direction and trying to protect the ones that were wounded.

"There's not a question in my mind that he was [intentionally] … left behind," she said.

Terry Chapman added, "Johnny would have wanted them to do just [what they did]."

Related content:

- New Details Reveal Airman John Chapman's Heroism at Roberts Ridge

- AF Cross Recipient: 'Remarkable' Fellow Airman Up for Medal of Honor

- Fallen Air Force Tech. Sergeant to Receive Medal of Honor in August

Nessel and Terry Chapman spoke to reporters outside Washington, D.C., a day ahead of John Chapman's Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House on Wednesday. They were accompanied by Chapman's former squadron commander, retired Col. Kenneth Rodriguez.

Chapman, 36, a combat controller assigned to the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, posthumously received the military's highest award, an upgrade of his Air Force Cross, for his actions on March 4, 2002. He is the first U.S. airman to receive the Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War and the 19th since the Air Force was established in 1947.

He was attached to a SEAL Team 6 unit during Operation Anaconda, a large-scale attempt to clear the valley of al-Qaida and Taliban forces. The team's task was to establish an outpost atop Takur Ghar.

The question of whether Chapman was abandoned is linked to a decision by his team leader, Senior Chief Special Warfare Operator Britt K. Slabinski. The SEAL, now a retired master chief, was awarded the Medal of Honor in May for his own heroism during the full-scale battle.

Slabinski led the SEAL Team 6 unit to which Chapman was assigned, known as Mako 30, back up the ridge after the team sustained heavy fire. During an initial drop-off attempt, Petty Officer 1st Class Neil Roberts had fallen out of the MH-47 Chinook helicopter. Looking to protect Roberts by calling in airstrikes from above, Chapman ran ahead of his teammates, braving fire from multiple directions before taking cover in a nearby bunker.

Roughly 20 minutes after the rest of the team moved toward him, members of the unit observed Chapman go down.

Slabinski eventually made the decision to pull his SEAL team out of the battle after taking heavy fire, which pushed them down the ridge. Though team members believed Chapman had died, evidence shows that he lived on.

"I believe firmly, as does everyone at this table, that every single man on that hill made the very best decisions they possibly could while bullets were flying, while people were getting wounded, [and] to say anything other than that would be a [mischaracterization] of what really went on," Rodriguez said Tuesday.

Members of Slabinski's team were interviewed during the Pentagon's 30-month-long investigation, giving officials more clarity on whether Chapman's actions merited upgrading his award to the Medal of Honor, according to an Air Force special tactics officer who was part of the investigation team.

Speaking on background during a briefing at the Pentagon on Thursday, the special tactics officer explained how the Air Force Special Operations investigative team and the Pentagon concluded that Chapman had lived and continued to fight after his presumed death.

It was determined that Mako 30, led by Slabinski, had come within 15 to 18 feet of Chapman's unconscious body -- the closest they could get to him in five-foot-deep snow while taking on fire from three directions in the dark.

The laser on Chapman’s gun had stopped moving, which is what led Slabinski and the team to believe the technical sergeant was dead while observing him through night-vision goggles, the special tactics officer said.

"Their mission was to not leave a man behind .. .so they're certainly not leaving anyone behind intentionally," he said.

When asked whether Slabinski might have mistaken Roberts' body for Chapman, the officer said it was unlikely.

Roberts' body was in "close proximity" to Mako 30's position, he said. But the team said they never saw it because of the terrain and snow level.

"What that tells you is that they were in thigh-deep snow, it was in the middle of the night, they were on NVGs, they probably don't really know what they're looking at," the special tactics officer said. "And they're being shot at from all sides."

Slabinski radioed a "possible killed in action," referencing Chapman as he called for backup and close-air support. In their testimony in 2002, members of Mako 30 questioned whether they had walked over Roberts somewhere on the mountainside.

"The fair answer is there was a lot of confusion everywhere," the special tactics officer said.

Always Proud

Nessel said she had seen the video feed of Chapman's last few minutes, which the Air Force released earlier this month on social media.

"It validates that he did do what we had thought he'd done," she said. "He was there by himself, but he fought [to the end] protecting his teammates."

What became available more recently to investigators was additional testimony, video and better technology to analyze the videos frame by frame, Rodriguez said.

"We were able to … finally substantiate what we had suspected all along. We knew that he did these heroic acts up front, but the final acts of heroism that we thought he did but couldn't prove it, we were finally able to prove it in the last couple years," he said.

Every American on Roberts Ridge did heroic things, Rodriguez said.

"John survived that additional wounding that he got, and he continued to fight on for an hour and then at a crucial moment, right at the end of his life, he sacrificed his life for the incoming quick reaction force when he could have hunkered down and said, 'Finally, the guys are coming in to get me,'" he said. "It's that last, full measure of devotion that he gave."

-- Oriana Pawlyk can be reached at oriana.pawlyk@military.com. Follow her on Twitter at @Oriana0214.