In 1996, the U.S. Air Force figured it needed to buy 11 C-130J cargo planes for about $840 million.

Today, the service's plans call for a total of 168 of the Lockheed Martin Corp.-made aircraft for $15.5 billion -- more than 18 times the original cost estimate.

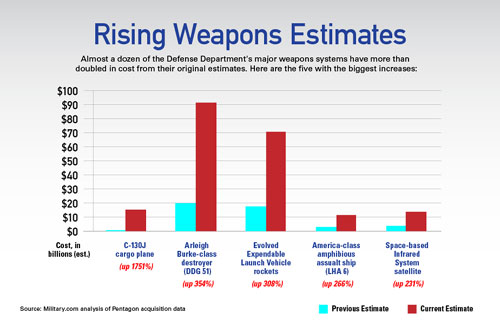

The Air Force's C-130J Super Hercules tops the list of major weapons systems that have had the largest increases in projected costs, according to a Military.com analysis of the Defense Department's latest acquisition data. The fluctuations highlight the shortcomings of budget forecasts for programs that are influenced not only by military officials in the Pentagon, but by lawmakers on Capitol Hill and contractors in their districts.

"With the Pentagon trying to retire the C-130 – they have too many – why are we buying more?" said Jeremiah Goulka, a former Rand Corp. analyst who writes for TomDispatch.com and the American Prospect. "Congress forces the military to not retire planes it needs to retire and to purchase extra planes it doesn't need."

Every year the Defense Department publishes cost estimates for major weapons systems in documents called Selected Acquisition Reports Summary Tables. The most recent report, released in May this year, included a portfolio of 78 systems projected to cost a total of $1.66 trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars.

That's a 2.7 percent increase in cost from last year's projections of $1.62 trillion for 83 systems. Compared to their previous estimates, the current systems have increased in overall cost by 21 percent, from $1.38 trillion.

The price tags of almost a dozen have more than doubled, from the Air Force's C-130 planes to the Navy's guided-missile destroyers to the Army's missile-defense interceptors.

|

Click on image to see larger version

TheNavy, for example, plans on spending $91.2 billion to buy at least 77 of the DDG 51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers – more than quadruple the initial estimate of $20.1 billion for 23 ships.

The service had planned to replace the ships, the first of which was commissioned in 1991, with a newer class of destroyers known as DDG 1000. But a few years ago, after sinking $10 billion into developing the Zumwalt-class, it changed course and decided instead to restart production of the Arleigh Burke-class and build a new version of the ship.

The decision to build more DDG 51s and stop production of DDG 1000s at just three ships was due in part to the global proliferation of short- and long-range missiles. The General Dynamics Corp. and Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc.-made DDG 51s are equipped with the Aegis combat system to detect and intercept missiles. The U.S. in recent years deployed four Arleigh Burke-class destroyers to Spain to help protect Europe from potential missile strikes by Iran or North Korea.

Similarly, the estimated cost of the Pentagon's Ballistic Missile Defense System has surged to $132 billion, an increase of 180 percent from the previous estimate of $47.2 billion. A test failure earlier this month of one of its components, the Ground-based Midcourse Defense System, designed to shoot down nuclear missiles from interceptors stored in silos, has raised concerns about its expense.

"We've reached a point now where we're making some critical budget decisions and may not be able to afford that luxury," Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., chairman of the Senate Appropriations Defense Subcommittee, said during a July 17 hearing. "What troubles me is this is a system that still hasn't been proven to be able to protect America."

Other programs whose cost estimates have at least doubled include the Air Force's Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle rockets (307 percent to $70.7 billion), the Navy's LHA 6 amphibious assault ships (266 percent to $11.3 billion), the Air Force's Space-based Infrared System satellites (231 percent to $13.7 billion), the Navy's Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (184 percent to $3.35 billion), the Air Force's Joint Direct Attack Munition (147 percent to $6.44 billion), the Army's Joint Tactical Networks (128 percent to $2.08 billion), the Air Force's Global Broadcast Service (123 percent to $1.11 billion), and the Navy's Tactical Tomahawk missile (116 percent to $7.11 billion).

But none has risen like the C-130J's.

The aircraft is the latest version of the Cold War-era C-130 Hercules. Since the 1950s Lockheed has built more than 2,400 of the medium-lift transport planes at its Marietta, Ga., site. The snub-nosed, propeller-driven plane is used for such missions as delivering troops and equipment, evacuating wounded personnel from the battlefield and attacking enemy positions with cannons and missiles.

Lockheed, the world's largest defense contractor, which derives 82 percent of its $47.2 billion in annual revenue from the federal government, says the C-130 has been in production longer than any other military aircraft and sold to more than 70 countries.

"The C-130J Super Hercules is built upon 60 years of Hercules history of developing and delivering a proven, unmatched, affordable workhorse that can support a wide variety of missions, around the world, at any time," Stephanie Sonnenfeld Stinn, a spokeswoman for the company, said in an e-mailed statement.

The Air Force – which has about 430 C-130s across the active, Guard and reserve forces – is buying more C-130J models than planned in part because of a decision to retire the older C-130E model by the end of fiscal 2014, according to a 2009 report from the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress.

A spokeswoman for the Air Force didn't immediately return an e-mail and telephone call seeking comment.

Goulka, who earlier this year wrote an essay on the history of the C-130, said the service has repeatedly replaced versions of the aircraft to buy newer, more problematic models. Efforts to cancel the program date to the Carter administration and have been undone by Congress amid lobbying campaigns from industry, he said.

"You have a smaller number of larger companies with more power who can then exert more influence in Congress by spending millions of dollars in lobbying and fund-raising every year and who famously build their planes and other military equipment in 435 congressional districts," he said.

The House of Representatives last week approved an amendment to its fiscal 2014 defense appropriations bill that would block the military from spending any money to cancel a separate program to upgrade the C-130 avionics system. The amendment was sponsored by Tim Griffin, R-Ark., where Chicago-based Boeing Co. has performed some of the work.

The Air Force's preference for the C-130J has already killed the C-27J program after officials said the service could not afford both because of budget cuts. The decision created a spat between active duty and Guard leaders.

The original plan was to field a fleet of 38 C-27Js across the service as part of the Joint Cargo Aircraft Program. Now, the Air Force is set to discard 21 of the aircraft that were just purchased from Finmeccanica's Alenia Aermacchi, an Italian defense company that pales in comparison to the size and influence of Lockheed.

Former Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Norton Schwartz told Congress in 2012 it cost $9,000 per hour to fly the C-27J and $10,400 to fly the C-130. However, the Ohio Air National Guard, which is one of four Guard units that fly the C-27J, had estimates of their own. Officials with the Ohio Guard disputed Schwartz's numbers, saying it cost $2,100 per hour to fly the C-27J and $7,000 per hour to fly the C-130.

Winslow Wheeler, a longtime defense analyst who's now a staff member at the Project On Government Oversight, a watchdog group in Washington, D.C., said the acquisition figures don't tell the whole story because many systems show a revised, not original, cost estimate.

For instance, the Pentagon in 2007, and then again in 2012, changed its assumptions about the cost and schedule of the Lockheed-made F-35 fighter jet, the military's most expensive acquisition program, in a process known as re-baselining, Wheeler said.

"That's burying a lot of the cost growth," he said in a telephone interview.

Still, Wheeler said, the case of the C-130J shows how program advocates deliberately sought a small number of aircraft at first, knowing that lawmakers would add more later, Wheeler said.

"They were sending them under the street lamp trying to attract Congress' attention, saying 'buy more,'" he said. "The ruse worked."