President Abraham Lincoln had a hunch.

Against the advice of his naval command, Lincoln made a fateful bet that a funny-looking little gunboat called the Monitor could take on the CSS Virginia, the ironclad doomsday machine that the Confederates had made out of the former steam frigate USS Merrimack. In so doing, Lincoln saved the Federal fleet and changed the course of the Civil War.

The bravery and determination of the Monitor’s all-volunteer crew made Lincoln’s gamble pay off in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862. However, 10 months later on New Year’s Eve, the floating fortress foundered in a storm off Cape Hatteras, N.C., and sank, taking 16 of the 63 sailors aboard to the bottom.

Two of the Monitor’s crewmen were buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full honors last Friday on the eve of the 151st anniversary of the first-ever clash between ironclads.

A Navy band played “America the Beautiful” at the gravesite as eight sailors in peacoats and “Dixie cup” caps bore each of the caskets containing the remains of Monitor crewmen who likely forever will be unknown.

A crowd of about 1,000, including nearly 200 descendants of the Monitor’s crew and Civil War re-enactors in period uniforms and hoop skirts, bowed their heads as a Navy bugler played “Taps,” the last note lingering in the blustery wind that swept the hillside.

Fittingly, the gravesite was in the cemetery’s Section 46, on a rise across from the Amphitheater and the Tomb of the Unknowns as the two will likely remain unknown. Section 46 also contains the remains of crew members of the two lost space shuttles, Challenger and Columbia, who were pioneers of another day.

At an earlier chapel service at Fort Myer, Va., Navy Secretary Ray Mabus noted that the Arlington burial was a break with Navy tradition which “holds that the site of a sunken vessel is a sacred burial ground, and that sailors who go down with their ships belong together” for eternity.

”But 11 years ago, when a team from the U.S. Navy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News , Va., raised the turret of USS Monitor from the depths, they were surprised to find the remains of two crew members,” Mabus said.

“We began the process to try and identify these men, but too much time had passed to match these two sailors to their names” among the 16 who were lost.

“This may well be the last time we bury Navy personnel who fought in the Civil War at Arlington,” Mabus said.

The Unknown

Descendants of the 16 who attended the ceremony agreed with the Navy’s decision that the marker eventually put up on the gravesite will list the names of all who went down with the ship that at first was mocked by the Confederates as a “tin can on a shingle.”

Cindi Nicklis Neumann, a great grand-niece of Seaman Jacob Nicklis, said that “despite modern science, it is still unknown whether the young seaman to whom I am related is one of the two being buried.”

“It is a wonderful testimony to our nation that we care so much about the sacrifices made on our behalf by its military. I have always been proud to know the armed services work diligently to identify personnel from recent actions so their families may gain a sense of closure,” Neumann told the Navy.

Andrew Bryan, whose great-great-great-uncle was Yeoman William Bryan, held out hope that further research might show that one of those buried was his relative.

Bryan showed the Portland (Me.) Press Herald a letter written to his parents by Yeoman Bryan about a month after the Monitor’s battle with the Virginia in which he expressed eagerness to renew the fight.

"Dear parents, I have just got a few minutes to write," Yeoman Bryan wrote. "We are going to have big time with the Southerens (sic) in a very few days and all our army is made another grand move on them again, and we expect orders every moment to start and make the Forts smell the Monitor again."

"I think it's definitely appropriate" for the burial to be at Arlington, Andrew Bryan said. "They were fighting for the Union and served the country. I don't think there could be a better place for them to be."

Those buried could be Bryan or Niklis, or maybe Ensign Willam Allen, Acting Ensign George Frederickson, or Robinson Hands and Samuel Lewis, both ranked Third Assistant Engineers.

Or, maybe Yeoman William Bryan, Officer’s Cook Robert Howard, Officer’s Steward Daniel Moore, First Cabin Boy Robert Cook, First Class Firemen Thomas Joice and Robert Williams, or Boatswain’s Mate Wells Wents (a.k.a. John Stocking).

Or, maybe William Allen and William Egan, both “Landsman,” the lowest rank given new recruits by the Navy at the time. Or, maybe George Littlefield, who had the rank of “Coal Heaver.”

“One of the things that should come out of this is that history is something that happened to real people,” said Anna Hollaway, curator at the USS Monitor Center of the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va., where the 150-ton, 30-foot diameter turret of the Monitor is on display.

“They really weren’t that different from us,” Holloway said of the 16 who drowned and all others who served on the Monitor. “Though 151 years separates us, you do see similarities to folks today.”

“It took some kind of moxie” to be part of the crew,” Holloway said, and “they were treated as celebrities” after slugging it out with the Virginia. “They couldn’t buy a drink wherever they went” and they were “comp’d” when they stayed at hotels, Holloway said.

What is known about the two buried at Arlington from examination of the remains by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command in Hawaii is that they both stood about 5-foot-6. One was about 20 years old and the other between the ages 35 and 40.

The older one was thought to be a pipe smoker, from the Popeye-like groove in his left front teeth where he clenched a pipe, and he had an arthritic back and likely limped because one leg was shorter than the other.

Government forensics specialists also constructed masks of what the two sailors may have looked like in life in the attempt to identify them, but to no avail.

Both were rough men with recently broken noses, probably the result of a drunken Christmas brawl ashore with British sailors in Newport News only a few days before the Monitor sank, Holloway said.

And they likely shared the timeless sailors’ gripes about the chow, the pay, the bone headedness of the officers, and the heat and mosquitos of a Virginian summer that were the constant refrain in letters home from shipmate George S. Geer.

"On Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays we have Bean Soupe (sic), or perhaps a bettor (sic) name would be to call it Bean Water. I am often tempted to strip off my shirt and make a dive and see if there really is Beans in the Bottom,” Geer wrote.

In another letter, Geer wrote that “we took the tempriture (sic) of several parts of the ship, or rather I did as I have charge of the Thurmomitor (sic), and found in my Store Room which is farthest astern it stood at 110, in the Engine Room 127, in the Galley where they cook and after the fire was out 155 – so you can see what a hell we have here.”

'Yankee Cheesebox'

But the crew was also “keenly aware that they were serving on an experimental vessel and they were aware of the skepticism about it,” curator Hollaway said. “People had been calling it an “Iron Coffin” in the North, and in the South the Monitor was derided as a “Yankee cheesebox on a raft,” Holloway said.

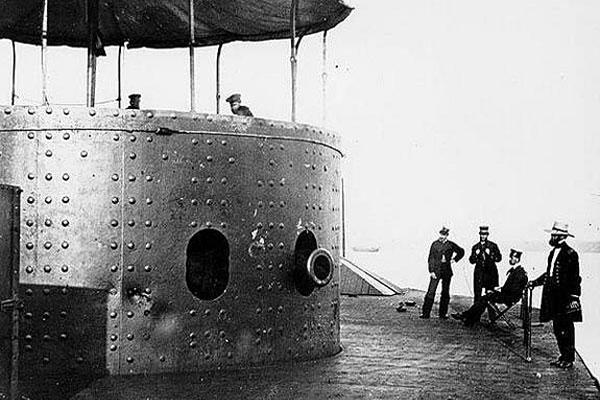

The odd design of the Monitor was the work of the crotchety genius John Ericsson, the Swedish-born naval architect. The ironclad he conceived had a revolving turret amidships mounted with two 11-inch Dahlghren guns that would hurl 240-pound missiles at the enemy.

The Navy brass thought Ericsson was mad, but Secretary of State William Seward arranged for an associate, Cornelius Bushnell, to present the design to Lincoln at the White House in late 1861.

Lincoln was aware from freed slaves that the Confederates were converting the Merrimack into the fearsome warship that would be the CSS Virginia at the Gosport works on James River, and he was desperately looking to counter the threat.

Lincoln pored over the design and is said to have told Bushnell: "Well, as the girl said when she put her leg in the stocking, I think there is something in it.”

The contract for the Monitor and its execution were in marked contrast to the creaky acquisitions process, cost overruns, and political gridlock of modern-day Washington. The low bid on the contract by Ericsson came in almost on time and at the cost of $275,000 (about $6,250,000 today).

The contract called for the Monitor to be built in 100 days and the workers at the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint, N.Y. (later the Brooklyn Navy Yard) did it in 101.

“Ericsson’s folly” was 179-feet in length, with a beam of 41-feet, whose main features were the massive revolving turret and a small armored pilot house forward. The Monitor was a low-riding affair with a deck barely above the waterline to present the smallest target to the enemy. She was meant to operate close to shore and would have to be towed at sea.

The Battles

The behemoth Virginia, 270-feet in length with sloping iron sides fashioned from rail ties, shipped anchor and sailed down the James River to Hampton Roads on the morning of March 9, 1862.

“When the Merrimac slowly steamed into Hampton Roads to confront the Federal blockading fleet, nothing like her had ever been seen before,” British author Amanda Foreman wrote in her account of the war, “A World on Fire.”

“Long and squat, she looked more like an iron champagne bottle than a ship. Her speed was terrible, but the armor plating made her invincible.”

The Virginia rammed and sank the USS Cumberland and blasted the 50-gun USS Congress onto the rocks and set her afire, while the USS Minnesota ran aground trying to get away from the Virginia’s onslaught. The Virginia retired to Norfolk, with plans to come back the next day to finish the Minnesota.

“There was cheering in Richmond and hysteria in Washington after the battle,” Forman wrote. “Lincoln called a special Cabinet meeting at which the new secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, made a spectacle of himself, ranting that every city on the eastern seaboard would now be laid waste” by the Virginia.

Stanton wanted ships to be sunk in the Potomac to block the Virginia from bombarding the capital. Lincoln and Navy Secretary Gideon Welles rejected Stanton’s advice and put their faith in the Monitor, which had arrived in Hampton Roads by tow shortly after midnight on March 9, 1862.

The Monitor took up a position behind the Minnesota, prepared to defend the ship from the next foray of the Virginia, but the Minnesota’s crew had a dim view of their savior.

“The guys on the Minnesota had seen what happened that day and they couldn’t believe that this little thing was going to save them. They spent the night hooting down at the Monitor,” said curator Holloway.

At about 8 a.m., the Virginia steamed straight for the Minnesota. Out from behind the Union frigate came the Monitor commanded by Lt. John Worden, driving between the Minnesota and her prey.

Crowds had gathered on the shoreline to watch the battle.

“It was a spectator sport back then,” Holloway said.

Maj. H. Ashton Ramsay, the chief engineer aboard the Virginia, later wrote that the ship “steamed across and upstream toward the Minnesota, thinking to make short work of her and soon to return with her colors trailing under ours.”

“We approached her slowly, feeling our way cautiously along the edge of the channel, when suddenly, to our astonishment, a black object that looked like the historic description, "a barrel-head afloat with a cheese-box on top of it," moved slowly out from under the Minnesotaand boldly confronted us.

“And now the great fight was on, a fight the like of which the world had never seen. With the battle of yesterday old methods had passed away, and with them the experience of a thousand years ‘of battle and of breeze’ was brought to naught. A new leaf had been turned, a virgin page on which to transcribe and record the art of naval warfare.”

The two ships blasted at each other for nearly four hours at close range, at times their hulls nearly touching, but with little effect. The Monitor’s shots glanced upwards off the Virginia’s sloping sides, and the Virginia’s bounced off the Monitor’s turrets, leaving huge dimples that could be seen in later photographs.

The Monitor’s crew was exhausted before the battle even began from arriving at midnight and staying up all night to get ready for the Virginia.

Lt. Samuel Dana Greene of the Monitor later wrote that “our shots ripped the iron of the Merrimac, while the reverberation of her shots against the tower caused anything but a pleasant sensation.”

"My men and myself were perfectly black with smoke and powder. All my underclothes were perfectly black, and my person was in the same condition. I had been up so long, and been under such a state of excitement, that my nervous system was completely run down. My nerves and muscles twitched as though electric shocks were continually passing through them. I lay down and tried to sleep. I might as well have tried to fly.”

Ramsay wrote of similar scenes aboard the Virginia: “The noise of the crackling, roaring fires, escaping steam, and the loud and labored pulsations of the engines, together with the roar of battle above and the thud and vibration of the huge masses of iron being hurled against us, altogether produced a scene and sound to be compared only with the poet's picture of the lower regions.”

The Monitor at one point withdrew to shallow water where the Virginia could not follow to tend to Lt. Worden, who had been temporarily blinded. The Virginia then also began to withdraw and did not return when the Monitor came out again. The Monitor’s crew sent up a cheer: “Hurrah for the little boat that is first in everything.”

The battle was considered a draw but The New York Times correspondent pronounced the Monitor victorious, reporting that it had “routed the famous rebel iron-clad floating battery.”

Ericsson, the ship’s designer, was livid. He argued that the Monitor would have sunk the Virginia in 30 minutes if the Navy had listened to him and used 30-pound powder charges for the shells instead of the 15-pound charges that were used.

The Monitor and Virginia would meet again on April 9, 1862, with Lincoln there to see it. Lincoln had gone to Hampton Roads to inspect the front lines but also to see Ericson’s nautical marvel. He was to become witness to the last encounter between the Monitor and the Virginia.

A tug took Lincoln out to the Monitor where “the 6-foot-4 Lincoln was an incongruity aboard the little ironclad,” according to the book “Lincoln and His Admirals,” by naval historian Craig Symonds. Lincoln was different than other Washington visitors, who blustered and gushed over the ungainly warship.

In contrast, “Lincoln was quiet and introspective, and asked practical questions. His (Monitor) guides were surprised and impressed that he ‘was well acquainted with all the mechanical details of our construction,’” Symonds wrote.

Lincoln asked for the crew to be assembled and then doffed his signature top hat.

“He walked past them, hat in hand, looking into their faces, and then thanked them for their service. As he left, they offered up three cheers,” Symonds wrote.

Later, still aboard the tug with Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln observed the Monitor and other Union ships bombard a ‘Confederate strongpoint ashore.

“As Lincoln watched, a large puff of black smoke curled over the woods behind Sewall’s Point and, almost in unison, those watching from the ramparts declared ‘There comes the Merrimac!’” Symonds wrote.

The other ships of the Union fleet pulled away at the sight of the Merrimac, as Lincoln had previously ordered, leaving the Monitor to face her alone – again.

“The Monitor held its ground, offering battle, and soon there was a ‘clear sheet of water’ between the two ironclads. But at that point, as Chase noted, ‘the great rebel terror paused – then turned back,’” Symonds wrote.

On May 9, 1862, the Virginia was scuttled by her crew in Norfolk to avoid capture by approaching Union troops, and the South never again seriously challenged the Union naval blockade.

Sunk

The last trip of the Monitor began under tow from the USS Rhode Island shortly after Christmas in 1862 under sunny skies and a light breeze, but the weather quickly turned and the seas rose off Cape Hatteras.

The Monitor’s paymaster, William Keeler, later wrote to his wife of “mountains of water rushing across our decks, the howling of the tempest, the bubbling cry of the strong swimmer in his agony and the whole panorama of horror which time can never efface from my memory.”

Launches from the Rhode Island managed to save most of the crew, who watched from the deck of the Rhode Island as the little red distress lantern finally went out and the Monitor sank in 230 feet of water, with the loss of the 16 sailors.

In an epitaph for the little ironclad, Monitor Surgeon Grenville Weeks later wrote in the Atlantic Monthly that the survivors were back ashore after two days and the loss of their ship in the storm that “seemed like some wild dream.”

“One thing only appeared real: our little vessel was lost, and we, who in months gone by, had learned to love her, felt a strange pang go through us as we remembered that never more might we tread her deck, or gather in her little cabin at evening. “

”We had left her behind us, one more treasure added to the priceless store, which Ocean so jealously hides. The Cumberland and Congresswent first; the little boat that avenged their loss has followed; in both noble souls have gone down. Their names are for history; and so long as we remain a people, so long will the work of the Monitor be remembered, and her story told to our children's children.”