Marine Maj. Steve Taylor, who had unknowingly suffered a concussion in Afghanistan after a roadside explosion, was at a takeout pizza dinner with his family at Camp Lejeune, N.C. There was some teasing over the toppings, which caused Taylor to fly into a rage.

“I realized -- what the hell am I doing, flipping out over toppings,” he said. “That’s when I realized I needed help.”

Taylor had trouble getting the help he needed at Lejeune and was eventually sent to the National Intrepid Center of Excellence at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. -- the military’s latest state of the art rehabilitation center dedicated to treating servicemembers afflicted with traumatic brain injury.

Following the success seen in TBI patients at the Intrepid Center, the Pentagon is working with a military charity, the Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund, to raise money and build nine satellite centers like it on military installations across the U.S.

TBI, one of the signature wounds of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, can take on a low profile in its milder forms that victims can’t or won’t acknowledge.

“Sometimes, people don’t even realize they have an issue,” said Gen. Ray Odierno, the Army’s chief of staff. When they do come to the realization, it can be just as hard for them to admit it and seek help.

“We’ve got to get to an environment that when they need help, they go get it.” Odierno told military families at the Association of the U.S. Army convention last week.

Army Reserve Sgt. Daniel Burgess only began to know something was wrong mentally when doctors weaned him off narcotics for the pain from the amputation of his right leg below the knee, the result of an improvised explosive device in Afghanistan. He also had suffered a concussion.

“I couldn’t remember to do things, I didn’t know what was what,” he said.

His wife, Genette, “was kind of like my little drill sergeant” through the crisis. With her help, he went into therapy.

Both Taylor and Burgess are among the more than 43,000 troops who have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury since 2002, according to Defense Department statistics. They are also among the few hundred who have benefited from the specialized treatment for TBI that the military is now seeking to expand in cooperation with the Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund.

The Intrepid Fund, inspired by the late New York real estate developer Zachary Fisher, began after 9/11 with gratuities to the families of servicemembers killed in the line of duty. In 2007, the Center for the Intrepid amputee and burn rehabilitation clinic was built at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas.

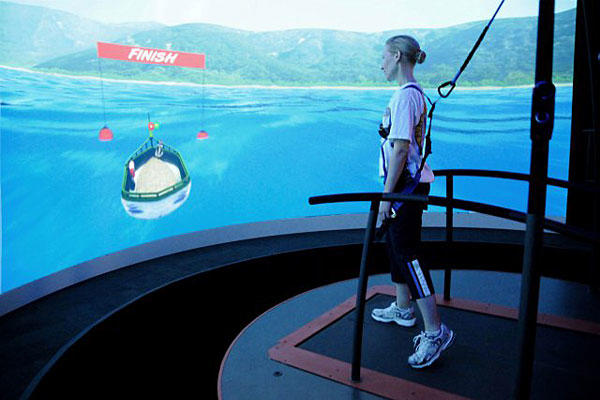

David Winters, president of the fund, said his group asked the Defense Department what they could do next after building the clinic. The result was the $70 million, state-of-the-art National Intrepid Center of Excellence that focuses on TBI at the Walter Reed.

“It was not built as a factory to keep pumping troops through,” Winters said. “From the ground up, it was specifically designed for research and treatment,” he said.

The fund now has a $100 million fund-raising campaign underway to build as many as nine Intrepid satellite centers at major military installations. Groundbreaking has already begun for TBI centers at Camp Lejeune and Fort Belvoir in Virginia, and planning is also underway for centers at Fort Campbell, Ky.; Fort Hood, Texas; Fort Bliss, Texas; Fort Bragg, N.C.; and Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash.

“Building the center here will enable us to provide localized advanced research and care for our Marines and sailors suffering from post-traumatic stress, traumatic brain injury and other related afflictions,” said Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford, after the groundbreaking for the center at Camp Lejeune in September.

The particular difficulty in diagnosing and treating TBI is that “if the brain injury is bad enough, you’re the last to know it’s a problem,” said Dr. James Kelly, a neurologist specializing in concussions who is the director of the Intrepid Center in Bethesda.

Consequently, involvement of the families is crucial to treatment, Kelly said. At the Bethesda center, patients are encouraged to bring their families, including children, who stay at the Fisher Houses on the grounds. One Navy SEAL brought eight relatives with him.

Since opening in 2010, the center has treated a total of about 350 patients. Usually, about 20 patients, all referred by their home providers, are on the grounds for stays of up to four weeks of intensive Monday through Friday sessions from 8:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.

“You can’t just treat the soldier, you have to treat the entire family,” said Army Surgeon General Lt. Gen. Patricia Horoho. The Bethesda center’s approach “manages the soldier as well as the family. It actually synchronizes behavioral health care with concussive care,” Horoho said at the AUSA convention last week.

The treatment starts when the patient walks through the door, is greeted by a nurse, and is ushered into a living-room setting for a session with a panel of specialists, including an internist, a family counselor, a neurologist, a psychologist and a social worker.

The focus is on “what do we need to know about you today, how can we start to help you. They get to say their story one time, not eight times” as often happens as patients are shuffled to new doctors and case workers at their home bases, Kelly said. “It elevates the level of interdisciplinary understanding.”

One of the first goals is dealing with sleep disorders common to TBI.

“Virtually everyone has it here. Virtually no one comes here sleeping normally,” Kelly said.

The patients also have access to alternative therapies such as art therapy, yoga and acupuncture.

“Mentally, it was exhausting but I noticed my memory started to click,” Taylor said about his stay at the Intrepid Center in Bethesda.

On Dec. 22, 2010, Taylor was serving with the 2nd Marine Regiment as an adviser to the Afghan National Security Forces. His MRAP hit an improvised explosive device on a mission in southwestern Afghanistan.

“Everybody in the vehicle was pretty much shook up” but otherwise uninjured and they continued with the mission, Taylor said. “I didn’t lose consciousness. I guess the shock waves affect people in different ways. I felt a little dazed.”

Within a week of the blast, he was experiencing fits of vomiting, which he attributed to the Afghan food and living conditions. But when he returned home, he had trouble sleeping, morning headaches and bouts of forgetfulness.

“I kind of thought it was old age creeping up,” said Taylor, 40, of Philadelphia. “I felt constantly in a haze, like I’d been drinking the night before, and I’m not a drinker.”

Then there were the fits of anger, which finally led him to seek help, but at Camp Lejeune “they couldn’t handle the problem.” There were waiting periods to see constantly changing therapists, and Taylor also had to handle his feelings of guilt.

“It’s kind of a stigma” for an officer to ask for help, Taylor said. “I was thinking ‘what about these junior Marines” who are also in line for appointments. “It’s a little harder for an officer to ask for treatment,” he said.

Lejeune eventually referred him to the Intrepid Center, where he immediately told the specialists that “I want to get my memory back; I want to get my speech back. I feel sore and tired every morning,” Taylor said.

After a battery of tests, “they found out I had sleep apnea.” With more treatment and counseling, “I’m a different person. My symptoms are not as severe,” and he has also learned coping mechanisms to deal with them, Taylor said.

Taylor’s injury was not obvious, even to him, but that was not the case with Sgt. Daniel Burgess. He was an Army psychological operations specialist attached to the 2nd Battalion, Fourth Marines, when he stopped on an improvised explosive device on Nov. 20, 2011, while on patrol near the flashpoint town of Sangin, Afghanistan.

In addition to losing his right leg below the knee, Burgess also suffered two compound fractures of the right hand in the blast in which the Afghan interpreter with the patrol lost an eye.

Burgess was sent to the Center for the Intrepid at Fort Sam Houston. While his physical wounds were being addressed, he also had to deal with the effects of the concussion.

“There were days I didn’t even want to get out of bed,” Burgess said.

At the Intrepid Center’s TBI clinic, he began to get help with short-term memory loss. “I started using my cellphone as an external memory,” Burgess said, and then there was the support of other troops in the clinic.

“All the other guys were going through the same thing,” he said. “That was some of the best therapy. Just listening to other people -- this guy is doing this, that guy is doing that. You just start noticing little things. I guess you could say it’s like group therapy.”

“But a lot of it is family” on the way to rehabilitation, Burgess said. “We have a saying in my family -- you cannot say I cannot do it. That’s the motto in our house.”

Burgess is now in the Warrior Transition Battalion at Fort Sam Houston, waiting to be discharged, “and I just got my running leg. I’m using it now all the time,” he said.

Burgess, 34, originally from Charleston, S.C., said he’s been in contact with the sheriff’s office of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, where he was on the special response team of the Corrections Department before being called up for duty in Afghanistan. They’ve promised to have a job waiting for him, Burgess said.