Air Force Master Sergeant Derrick Porter is now in his 22nd year of active duty as a jet engine technician in Arizona, a model service member. But he doesn't forget his family's humble origins, and the life lessons that have led him to a successful career. He often recalls the words of his grandmother, who told Derrick and his two older brothers while they were growing up, "We have no reason to hate anyone," and the example set by his hardworking grandfather. His story — his family's story — is a reminder that determination and self-reliance lead to success.

Grandmother Rheumonia

Derrick gives much of the credit for his achievements to his grandmother Rheumonia (pronounced Romania) Arnold, who took in Derrick, his mother and his brothers after his parents separated. While their mother held down two jobs, Rheumonia raised the boys in Atlanta, Georgia, where she lived almost all of her life. And it wasn't just Derrick and his brothers — Rheumonia helped out her other daughters and daughters-in-law by looking after up to eight grandchildren in her home, while their mothers worked.

Rheumonia was not only good to her daughters-in-law, but to her granddaughters-in-law as well. Derrick's wife, Sharon, remembers her as a woman who refrained from judging people and "radiated love." "Rheumonia just embraced everybody," Sharon says.

Derrick carried Rheumonia's lessons through life, much to the success of his military career. "[My grandmother] taught us a lot of adjustment skills, as far as accepting life the way it is … how to live a comfortable life and get along with others, without confrontation," Derrick says. "We didn't really talk much about [schools being segregated]. It was just one of those things that happened."

As a child, Derrick walked with his brothers to the school designated for black children in Fayetteville, Georgia. He didn't experience integration until 1970, when he entered the third grade. What was a milestone in the civil rights movement for most left Derrick and his brothers unfazed; he cannot recall any details from the first day he was allowed to walk on campus and sit in a classroom with children of all ethnicities.

Rheumonia passed away in September 2001, and was laid to rest on the day before Derrick reached a milestone 21 years of active duty.

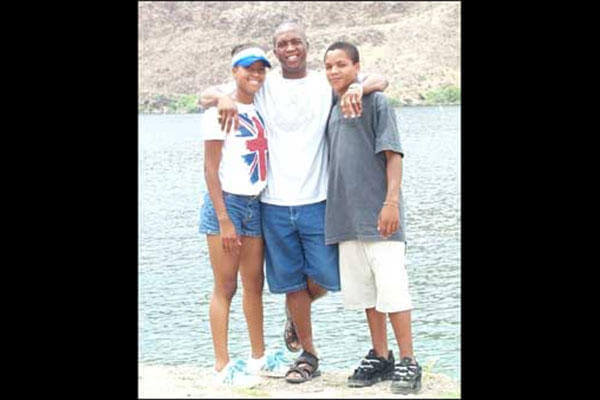

Rheumonia's strength is just one of the multiple wells of family history that Derrick and Sharon Porter draw from when teaching their two teenage children about their heritage. Their oldest child, Chelsi, 17, is in the top five percent of her class in academic achievement, and is an honor student. She also plays varsity softball and is on her school's student council. Varay, 14, is also in the honors program and looks forward to his father's retirement from the Air Force, so that they can spend more time together — as when Derrick recently helped coach his basketball team.

From Slavery to Freedom

Chelsi and Varay's lineage spans two continents: America on their father's side of the family and England on their mother's side. One of the richest sources of heritage in the family is Derrick's great grandfather, Arthur Chester Arnold. When he was born on September 15, 1881, slavery had been abolished for more than 15 years — but not extinguished.

When Arthur was a boy, some plantation owners still sought to maintain authority, as well as profit margins, by working the children of black laborers without pay. Black families fought against the practice, but plantation owners appealed to the courts, which could refer to such children as "apprentices."

All of his life, Arthur called it for what it was: slavery.

As a child, he tried several times to escape, as had many slave laborers before him. "He used to tell us about the things that he went through," says Derrick. "A lot of the beatings … the whippings and running away. [Despite] everything that he went through as a child, I could never recall one day that I ever heard him say that he hated anybody. He was a very Christian man."

Although Derrick is unable to mark a specific date when his great-grandfather finally became a free man, patience paid off as Arthur became an adult, thus leaving the plantation owners unable to force him to work. In addition to being a farmer, Arthur built and ran a blacksmith shop, practicing his craft until his death in 1985 at age 105.

Outside of his trade, Arthur held a variety of interests. "Basically, he was a self-taught dentist (and) medicine man," Derrick says. "Any time we had tooth problems … he did it, he pulled the teeth. Any time we had injuries, or cuts or wounds … he would go down into the woods and come back with different leaves … he'd cook these things up and administer natural painkillers."

For more than 80 years, Arthur served as head deacon as well as in other capacities at the Edgefield Baptist Church in Fayetteville. He was one of the church's founders. He drove his car until he was 103, and shortly before his passing, he still cut his own grass, went for walks, worked in his shop and read the Bible daily. "He was very mentally sharp," Derrick said.

Throughout Arthur's life, folks gathered on his front porch in Fayetteville to hear the stories of the slim, six-foot-tall man. Neighbors, family and newspaper reporters sat transfixed, sometimes for hours. Often, Georgia state troopers pulled over to hear history recapped by one of the state's most famous fellows. One officer offered him an official state trooper hat, which Arthur wore every day during his last years.

Before Derrick and Sharon reported for duty in England (where Sharon was born) in 1984, they made the rounds visiting Derrick's family, with their two-month old daughter Chelsi in tow. It would prove to be the last time the family met with Arthur. Sharon sighs as she recalls meeting the man everyone called "Papa."

"I remember looking at his hands. He had the most beautiful hands," Sharon says. "They were very old with lots of lines and I just think about how many stories those hands could tell (about) everything they had done … when he was holding Chelsi in his arms … I just felt in awe of that … that his blood was running through her veins."

Almost from the time Chelsi was born, Sharon has taught preschool. She became drawn to the profession, she says, because of what she went through as a little girl growing up in England. She moved in with her grandparents when she was five years old, and her grandmother Kathleen Dove raised her for several years. Being one of only three black children in school, (the other two were her brothers), Sharon preferred not to go outside to play.

"It was just cruel out there," she says quietly. "A lot of racial name-calling. There was no diversity … it was really lonely and horrible, absolutely horrible. I never fitted in at my school. Never. I even felt that sometimes teachers didn't want to be around me."

Kathleen, who neighbors described as always "having a string of grandchildren trailing behind her," wasn't shy about standing on her front lawn to shake her finger at prejudice, no matter how young. "She would tell (the children) to stop being mean and not to call names. My Nanny told me to stay away from them." Sharon says.

During lighter moments, Kathleen took Sharon and the six other grandchildren, who stayed with her during daylight hours, on long walks through the woods and across the cornfields. "We just thought that was the neatest thing," Sharon says. We would just walk and then run and run and run."

Sharon most remembers her grandmother's sense of humor and imagination. Kathleen Dove passed away in November of 2001.

Only when she was reunited with her mother and stepfather, living and attending school at R.A.F. Woodbridge base in England, did she begin to excel academically. Off-base living, however, presented more of the same issues she faced in her young childhood. Being stationed in Eglin Air Force Base in Florida was one of those times.

Her stepfather, a firefighter, worked a 24-on/24-off shift. During his off hours, he worked as NCO club manager to support the family. Sharon's mother, Dianne Bronson, stayed at home with Sharon, her sister and three brothers. She later worked at A.A.F.E.S. on base, where she has been employed for much of her life. With Sharon's stepfather juggling two jobs and her mother looking after five children, heart-to-heart talks between Sharon and her parents were scarce.

"It was my white mom and my black step-dad and all of us little kids running around. It was horrible until we moved on base again," Sharon said. "My children know that military people are different, and are warmer and more accepting. They do notice a difference."

Telling Stories

Tucked away from the street, the Porter's porch doesn't exactly beckon friends and neighbors to "set a spell." That doesn't stop Derrick and Sharon, however, from carrying on Arthur Chester Arnold's most loved tradition with their children.

"We tell a lot of stories," Sharon says. "I think the kids probably know every good and bad thing we did when we were little kids. We spend a lot of time just laying around and we tell them funny stories about when we were growing up, so that they realize 'this' is part of me, and 'this' is also part of me and it makes me a really unique person."