The Medal of Honor is the United States of America's highest military honor for personal acts of valor above and beyond the call of duty. The medal is bestowed by the president of the United States in the name of the U.S. Congress to U.S. military personnel only. The veterans profiled below are only a few among those who have received the medal -- for a full list of all recipients, visit the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

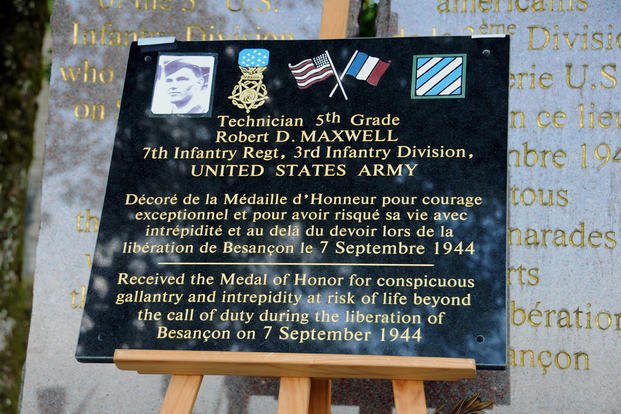

Robert Dale Maxwell

The oldest current living Medal of Honor recipient is a former Army soldier who received the medal in recognition of his actions in World War II. Born Oct. 26, 1920, Maxwell served as a technician fifth grade with the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division. Part of the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, Maxwell was wounded during the Battle of Anzio in January 1944 and rejoined his unit for the invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon) in August 1944. On Sept. 7, near Besançon, Maxwell performed the act that would be commemorated by his Medal of Honor:

Technician 5th Grade Maxwell and 3 other soldiers, armed only with .45-caliber automatic pistols, defended the battalion observation post against an overwhelming onslaught by enemy infantrymen in approximately platoon strength, supported by 20mm. flak and machine-gun fire, who had infiltrated through the battalion's forward companies and were attacking the observation post with machine-gun, machine pistol, and grenade fire at ranges as close as 10 yards. Despite a hail of fire from automatic weapons and grenade launchers, Technician 5th Grade Maxwell aggressively fought off advancing enemy elements and, by his calmness, tenacity, and fortitude, inspired his fellows to continue the unequal struggle. When an enemy hand grenade was thrown in the midst of his squad, Technician 5th Grade Maxwell unhesitatingly hurled himself squarely upon it, using his blanket and his unprotected body to absorb the full force of the explosion. This act of instantaneous heroism permanently maimed Technician 5th Grade Maxwell, but saved the lives of his comrades in arms and facilitated maintenance of vital military communications during the temporary withdrawal of the battalion's forward headquarters.

Maxwell currently lives in Bend, Oregon, the only living Medal of Honor recipient in that state, and is the director of the nonprofit Bend Heroes Foundation.

William Kyle Carpenter

Born Oct. 17, 1989, Kyle Carpenter is a retired Marine who has been the youngest-living service member to receive the Medal of Honor thus far for his actions in Marjah, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, in 2010. Carpenter was the youngest living Medal of Honor recipient at the time he received it. After enlisting in 2009, Carpenter was assigned to Fox Company, 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, Regimental Combat Team One, 1st Marine Division (Forward), 1st Marine Expeditionary Force (Forward), in Helmand Province in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

On Nov. 21, 2010, while joining his team to fight off a Taliban attack in a small village the Marines had nicknamed Shadier between two villages nicknamed Shady and Shadiest, he suffered severe injuries to his face and right arm from the blast of an enemy hand grenade, including multiple shrapnel wounds and the loss of his right eye. According to the official Medal of Honor citation:

Lance Corporal Carpenter and a fellow Marine were manning a rooftop security position on the perimeter of Patrol Base Dakota when the enemy initiated a daylight attack with hand grenades, one of which landed inside their sandbagged position. Without hesitation and with complete disregard for his own safety, Lance Corporal Carpenter moved toward the grenade in an attempt to shield his fellow Marine from the deadly blast. When the grenade detonated, his body absorbed the brunt of the blast, severely wounding him, but saving the life of his fellow Marine.

In March 2011, the South Carolina Legislature passed a resolution recognizing Carpenter's service, noting that he "suffered catastrophic wounds in the cause of freedom" and "has shown himself worthy of the name Marine." Corporal Carpenter received the Medal of Honor on June 19, 2014.

Hiroshi H. Miyamura

The Army veteran, also known as Hershey Miyamura, is an unusual Medal of Honor recipient. Although he gained recognition for his heroic actions in the Korean War, official announcement that he had received the Medal of Honor was held back while he was a prisoner of war in Korea.

Born in New Mexico to Japanese immigrant parents in 1925, Miyamura initially joined the Army in January 1945, and stayed in the Army Reserve after World War II. He was recalled to active duty during the Korean War, and was recognized for his actions on April 24–25, 1951, near Taejon-ni, Korea, while serving as a corporal in the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division:

Cpl. Miyamura, a member of Company H, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. On the night of 24 April, Company H was occupying a defensive position when the enemy fanatically attacked, threatening to overrun the position. Cpl. Miyamura, a machine-gun squad leader, aware of the imminent danger to his men, unhesitatingly jumped from his shelter wielding his bayonet in close hand-to-hand combat killing approximately 10 of the enemy. Returning to his position, he administered first aid to the wounded and directed their evacuation. As another savage assault hit the line, he manned his machine gun and delivered withering fire until his ammunition was expended. He ordered the squad to withdraw while he stayed behind to render the gun inoperative. He then bayoneted his way through infiltrated enemy soldiers to a second gun emplacement and assisted in its operation. When the intensity of the attack necessitated the withdrawal of the company Cpl. Miyamura ordered his men to fall back while he remained to cover their movement. He killed more than 50 of the enemy before his ammunition was depleted and he was severely wounded. He maintained his magnificent stand despite his painful wounds, continuing to repel the attack until his position was overrun. When last seen he was fighting ferociously against an overwhelming number of enemy soldiers.

Miraculously, Miyamura survived the battle and became a prisoner of war for 28 months. His was the first Medal of Honor to be classified top secret. Brig. Gen. Ralph Osborne would later explain during the official announcement of Miyamura's medal, "If the Reds knew what he had done to a good number of their soldiers just before he was taken prisoner, they might have taken revenge on this young man. He might not have come back." Miyamura was eventually re-repatriated to the United States in 1953 and honorably discharged from the military shortly thereafter. His medal was presented to him by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in October 1953 at the White House.

Bennie G. Adkins

Still going strong at over 80 years old, Adkins (born Feb. 1, 1934) was serving as an intelligence sergeant with Detachment A-102, 5th Special Forces Group in the Army when he gained recognition for his actions during combat operations at Camp A Shau in Vietnam from March 9-12, 1966:

When the camp was attacked by a large North Vietnamese and Viet Cong force in the early morning hours, Sergeant First Class Adkins rushed through intense enemy fire and manned a mortar position continually adjusting fire for the camp, despite incurring wounds as the mortar pit received several direct hits from enemy mortars. Upon learning that several soldiers were wounded near the center of camp, he temporarily turned the mortar over to another soldier, ran through exploding mortar rounds and dragged several comrades to safety. As the hostile fire subsided, Sergeant First Class Adkins exposed himself to sporadic sniper fire while carrying his wounded comrades to the camp dispensary ...

During the early morning hours of March 10, 1966, enemy forces launched their main attack and within two hours, Sergeant First Class Adkins was the only man firing a mortar weapon. When all mortar rounds were expended, Sergeant First Class Adkins began placing effective recoilless rifle fire upon enemy positions. Despite receiving additional wounds from enemy rounds exploding on his position, Sergeant First Class Adkins fought off intense waves of attacking Viet Cong. Sergeant First Class Adkins eliminated numerous insurgents with small arms fire after withdrawing to a communications bunker with several soldiers. Running extremely low on ammunition, he returned to the mortar pit, gathered vital ammunition and ran through intense fire back to the bunker. After being ordered to evacuate the camp, Sergeant First Class Adkins and a small group of soldiers destroyed all signal equipment and classified documents, dug their way out of the rear of the bunker and fought their way out of the camp. While carrying a wounded soldier to the extraction point he learned that the last helicopter had already departed. Sergeant First Class Adkins led the group while evading the enemy until they were rescued by helicopter on March 12, 1966.

During the 38-hour battle and 48 hours of escape and evasion, fighting with mortars, machine guns, recoilless rifles, small arms and hand grenades, it was estimated that Sergeant First Class Adkins killed between 135 and 175 of the enemy while sustaining 18 different wounds to his body.

Adkins retired from the Army in 1978 and has been CEO of Adkins Accounting Service Inc., in Auburn, Alabama, for 22 years. Adkins has been married to his wife, Mary, for 59 years, and together they have raised five children.

Leo Keith Thorsness

In 1966, then-Major Leo Thorsness was assigned to the Air Force's 357th Tactical Fighter Squadron in Thailand as a "Wild Weasel," charged with destroying enemy surface-to-air missiles and antiaircraft radar before the main strike force reached the target, thus protecting the strike force. On April 19, 1967, it was on one of these "Wild Weasel" missions that Maj. Thorsness gained recognition and was selected to receive a Medal of Honor:

As pilot of an F-105 aircraft, Lieutenant Colonel Thorsness was on a surface-to-air missile suppression mission over North Vietnam. Lt. Col. Thorsness and his wingman attacked and silenced a surface-to-air missile site with air-to-ground missiles and then destroyed a second surface-to-air missile site with bombs. In the attack on the second missile site, Lt. Col. Thorsness’ wingman was shot down by intensive antiaircraft fire, and the two crewmembers abandoned their aircraft.

Lt. Col. Thorsness circled the descending parachutes to keep the crewmembers in sight and relay their position to the Search and Rescue Center. During this maneuver, a MIG-17 was sighted in the area. Lt. Col. Thorsness immediately initiated an attack and destroyed the MIG. Because his aircraft was low on fuel, he was forced to depart the area in search of a tanker.

Upon being advised that two helicopters were orbiting over the downed crew’s position and that there were hostile MIGs in the area posing a serious threat to the helicopters, Lt. Col. Thorsness, despite his low fuel condition, decided to return alone through a hostile environment of surface-to-air missile and anti-aircraft defenses to the downed crew’s position. As he approached the area, he spotted four MIG-17 aircraft and immediately initiated an attack on the MIGs, damaging one and driving the others away from the rescue scene. When it became apparent that an aircraft in the area was critically low on fuel and the crew would have to abandon the aircraft unless they could reach a tanker, Lt. Col. Thorsness, although critically short on fuel himself, helped to avert further possible loss of life and a friendly aircraft by recovering at a forward operating base, thus allowing the aircraft in emergency fuel condition to refuel safely.

Lt. Col. Thorsness’ extraordinary heroism, self-sacrifice and personal bravery involving conspicuous risk of life were in the highest traditions of the military service, and have reflected great credit upon himself and the U.S. Air Force.

Though Thorsness was recognized with the Medal of Honor in 1967, he did not receive it until 1973. Eleven days after the mission cited above, he was shot down over North Vietnam and captured, along with his electronic warfare officer, Capt. Harold Johnson (who had also been with Maj. Thorsness on April 19 and was awarded the Air Force Cross for his part in that mission). Col. Thorsness and Capt. Johnson were released on March 4, 1973, after six years as prisoners of war. Thorsness retired on Oct. 25, 1973.

Veterans Day Features on Military.com

- 8 Ways to Express Appreciation on Veterans Day

- Veterans Day Discounts and Freebies

- Celebrity Veteran Profiles

Stay on Top of Your Veteran Benefits

Military benefits are always changing. Keep up with everything from pay to health care by signing up for a free Military.com membership, which will send all the latest benefits straight to your inbox while giving you access to up-to-date pay charts and more.