Military.com Fitness is starting a new section where we reach out to various medical and science professionals to get advice on fitness, injury prevention, injury rehabilitation, nutrition and many other topics that will help our readers.

Many emails ask our writing team about running faster, running injuries and how to prevent them. I am pleased to introduce Dr. Michael Cassatt, who is a former Navy corpsman and now a doctor of sports medicine. Cassatt explains how to prevent running injuries:

Injuries in runners are common. Injuries from the waist down can range from one in four runners, to two in three runners, depending on training volume. Most injuries are preventable, given a good training plan, quality running form and a few specific exercises to help supporting muscle groups. There are a number of injuries that can occur from running, including:

- Hip: Hip flexor tendinopathy, impingement and bursitis.

- Knee: Iliotibial band syndrome, runner's knee (patellar tendinopathy) and meniscal tears.

- Tibia: Shin splints, compartment syndrome and stress fractures.

- Foot and ankle: Achilles' tendinopathy, peroneal tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis.

The good news is that by following the steps below, these injuries can be reduced greatly or even eliminated.

Build volume for a lifetime of running. One of the most common mistakes made is attempting to build volume too quickly. The general rule is to build no more than 10% per week. Adding miles at 10% per week is probably fine at the lower end of mileage (0-15 miles per week), but as overall volume increases, the increases per week should slow. Ideally, there should be weeks with little to no increase in mileage after getting to 20-30 miles per week. Again, the goal is to build slow enough to allow muscles and tendons to adapt to this new strain without incurring injury beyond the body’s ability to repair between workouts.

Slow it down. Building volume means focusing on volume. It is not the time to incorporate speed or intensity. Attempting to build volume at higher intensities greatly increases the risk of injury. This is where the concept of periodization comes in. Just like building a house, you have to focus on the foundation first.

Volume is the foundation to build the muscle, tendon and cardiovascular changes needed to support later training in intensity while limiting injury. During a volume-building period, the majority of runs should be done at 2-3 minutes per mile slower than your best one-mile time. They should feel too easy if done correctly, and you should be able to carry on a conversation while running.

Run more often. Attempting to compress all of your weekly volume into 2-3 runs is a recipe for injury. Try taking the total mileage in a week and dividing it into 5-6 runs, alternating between an easy day and a higher-volume day.

Recovering from two four-mile runs is easier than one eight-mile run, but it still causes adaptation in the body’s muscles, tendons and cardiovascular system. As long runs get longer, consider breaking them into a morning and afternoon run. The cumulative training effect will be similar while reducing the risk of injury.

Increase your cadence. Cadence is calculated by counting the number of steps for one foot in a minute and multiplying by two. Elite-level runners typically have cadences in excess of 180 steps per minute. Increased cadence has been shown to decrease injury rates by reducing ground forces through the lower leg. Increasing cadence promotes a midfoot strike rather than contacting the ground with the heel first, and it also reducing the forces transmitted through the knee.

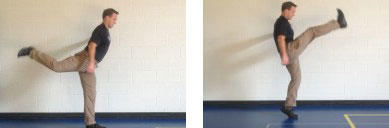

Stretch. Dynamic stretching before and static stretching after. Newer studies show decreases in strength when static stretching prior to exercise. (The type of stretching we all grew up with -- starting a stretch and then holding it for a period of time) A dynamic warmup prior to running, involving controlled movement through a complete range of motion for each joint, is better.

After running, the usual stretching for 20-30 seconds per body part, without bouncing, is acceptable. Maintaining flexible hamstring and calf muscles will help with injury prevention.

|

Front-to-back hip swing: Swing your hip in a comfortable arc from full flexion to full extension for 10 repetitions for each leg. |

|

Side-to-side hip swing: Swing your hip in a comfortable arc from across your body to completely away from your body for 10 repetitions each leg. |

Keep a strong core and glutes. The core (abdominal and lower-back muscles) is the foundation for movement and need to be strong to help control movement of the legs. The glutes, specifically the gluteus medius muscle, is responsible for controlling thigh rotation, tracking of the patella (kneecap) and controlling the knee.

A weak gluteus medius has been found to contribute directly to conditions such as IT band syndrome, patellar tendinopathy (runner’s knee), shin splints, Achilles' tendinopathy and plantar fasciitis. This is particularly true for soldiers who run on uneven surfaces or in soft sand. As these muscles fatigue during the run, pronation of the foot increases, the angle of the knee changes and stride length increases. All of which increase injury rate. The goal is to strengthen enough to function correctly throughout your entire run.

|

Front plank: Can be performed on forearms, hands or, for a greater challenge, a Bosu ball. |

|

Side plank: Can be performed on forearm, hand and can be combined with hip abduction for gluteus medius strengthening. |

|

Hip abduction from “all-fours” position: aka Dirty Dogs. Focusing on good form, try working up to three sets of 30, lifting the knee/leg out to the side 90 degrees. |

Know when to back off. By reducing intensity, increasing frequency, slowly building volume and increasing cadence, delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) should be reduced greatly or eliminated. Any pain that occurs during running or immediately after is often a warning of injury. Continuing to run could increase the injury substantially and prolong the time needed for recovery.

Stop running when this type of pain occurs, take a reasonable rest period and, if it returns, seek help. Remember you are training for a career and hopefully for a lifetime of running. Take it slow, use common sense and use these steps to help keep you healthy.

Stew Smith is a former Navy SEAL and fitness author certified as a Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) with the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Visit his Fitness eBook store if you’re looking to start a workout program to create a healthy lifestyle. Send your fitness questions to stew@stewsmith.com.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for fitness and basic training tips, or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.