During a recent field exercise, a Marine headquarters group set up an expeditionary operations center and facilities, then hung camouflage netting over every building and structure -- a time-honored Marine Corps practice that has fallen out of popularity during recent wars, in which the enemy did not possess aircraft.

Unit leaders tested the effectiveness of the disguise by pulling up Google Maps for an overhead view of their location, only to discover that concertina wire strung around more sensitive sites reflected sunlight and effectively circled key targets for a notional enemy.

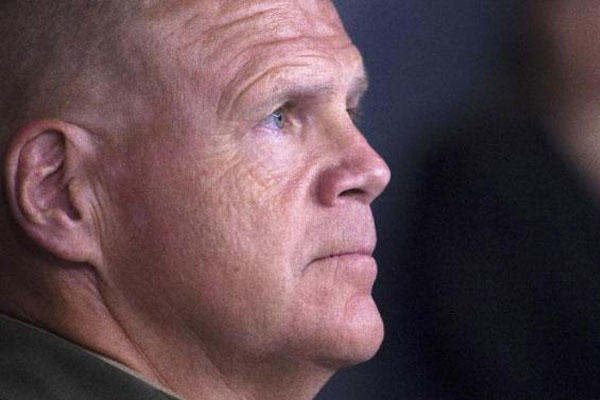

"You've got to look at yourself, and you've got to change the way you're thinking," Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Robert Neller told an audience at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on Tuesday.

To prepare for a potential future high-end conflict, Neller wants Marines to excel at low-end defense measures -- tools as simple as camouflage -- in anticipation of interference from a high-tech enemy.

"We've been operating out of fixed positions," Neller said of the two land wars the Marines fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. "We have not moved across the ground, we have not maneuvered, we have not lived off the land. We've been eating at chow halls and drinking Green Beans coffee."

Neller said Marines were relearning simple skills such as effective camouflage measures to mask the shape of a helmet and disguise the contours of a face. At the same time, he said, troops were being told in field training to practice digital camouflage measures: to leave behind GPS-enabled devices that could reveal their location, including smartphones, and focus on time-honored warfighting basics.

"You're going to live out of your pack. You're going to dig a hole, you're going to camouflage, you're going to turn off all your stuff, and you're going to sit there and try to sleep," Neller said. "And you're going to try not to make any noise, and you're going to have absolutely no signature. Because if you can be seen, you can be attacked."

Neller noted that Navy leaders in recent years have launched similar efforts to prepare the service for a future fight in which communications might be jammed or unreliable, and networks, GPS and other technology might come under attack.

At the initiative of former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert, he said, the Naval Academy had resumed teaching celestial navigation after it was dropped from the curriculum, in recognition of a future in which high-tech navigational tools are compromised. The Navy has also looked at other measures, such as turning off radar, to reduce or eliminate electromagnetic signature.

There is a balance. When working with inherently high-tech platforms such as the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter, which will replace three aging Marine Corps fighter aircraft over the next dozen years, Neller said it was important to recruit and retain Marines who could find ways to continue operating despite things not going according to plan.

"We have to find people who have the initiative and the aggressiveness and the intelligence to understand what they have to do in the absence of certainty," Neller said. "There is never certainty in war."

-- Hope Hodge Seck can be reached at hope.seck@military.com. Follow her on Twitter at@HopeSeck.