SEATTLE -- If members of Coast Guard Sector Puget Sound’s prevention department are doing their jobs, you’ll never hear about it.

And that’s a good thing.

“Sector Puget Sound Prevention Department has a rich history in providing for a clean, safe, secure and economically viable Pacific Northwest maritime region,” said Master Chief Petty Officer Randy P. Sorge, a member of Sector’s Facilities and Container Inspections Branch. “Called ‘America’s Sector,’ it is the homeport to the largest commercial fishing fleet for Alaska, the largest passenger ferry system in the country, and one of the busiest commercial ports on the West Coast.”

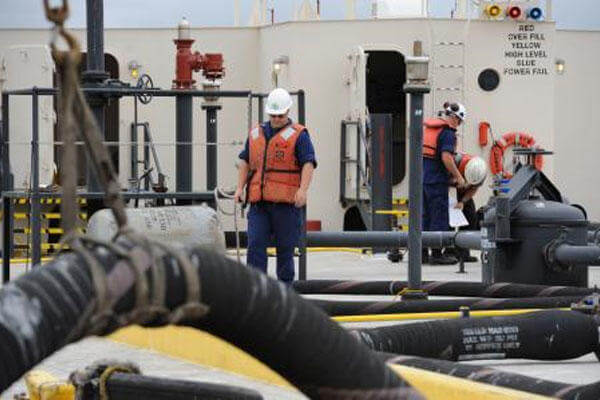

Coast Guard marine inspectors enforce regulations that aim to prevent hazardous work environments, terrorist attacks, major pollution incidents and other catastrophic events along U.S. coastal waterways.

Every day, marine science technicians assigned to the prevention department at Sector in Seattle inspect local marine facilities and incoming cargo for safety, security and hazardous materials. They also board and inspect foreign-registered cargo ships to ensure compliance with U.S. laws and international treaties.

“These are all critical infrastructures,” said Petty Officer 1st Class Christopher M. Olson, a member of one of Sector’s inspection teams. “Our whole mission in prevention is to help the industry prevent a major catastrophe.”

Sector Puget Sound personnel regulate 118 marine facilities in the region. These range from small ferry docks to multi-billion dollar cargo ship terminals. In order to stay in operation, each facility must pass an annual inspection and at least two separate spot checks, one planned in advance and the other unannounced.

“We’re just helping them help themselves,” said Olson. “What it all boils down to is personal and environmental safety.”

An annual inspection can take several hours. It includes a thorough examination of the property for safety and security violations, such as ineffective fire-fighting equipment, inadequate warning signs about potential safety hazards, and vulnerable spots in the property’s security perimeter.

Spot checks are less extensive and can include questioning duty security guards on emergency procedures and security policies.

Port security grew in importance after 9/11, said Olson. The industry understands the need for safety.

“A lot of these facilities are now in an urban area,” said Petty Officer 2nd Class Peter A. Blunk, another member of Sector’s inspection teams.

The safe practices of these facilities are critical because hazardous material incidents have the potential to kill thousands of people, he said.

The Port of Seattle, located downtown in the city of more than 620,000, is listed as the ninth largest port in North America based on total units of cargo capacity. According to its website, Seattle port businesses generate $17.6 billion in revenue each year.

Inspectors work with various agencies such as the National Response Center and the Transportation Security Administration to ensure facilities are able to operate in a safe manner.

They also coordinate with another group dedicated to protecting local maritime resources, Sector’s incident management division.

The incident management division’s primary responsibility is responding to spills and pollution incidents after they occur. Occasionally, though, they take on the role of prevention.

When responders are called to the scene of a pollution incident, their first concern is preventing the situation from getting worse.

“Our main goal is to make sure the source is secured to make sure it’s not still discharging,” said Petty Officer 2nd Class Nicholas P. Debrum, a marine science technician assigned to IMD. “Then we recover any discharged product to mitigate the environmental impact.”

In some cases, responders must take action to prevent discharges of hazardous products into the water before they occur.

“Every boat has the potential for oil to be onboard,” said Debrum. “When a boat is considered derelict or sinks, we’re always concerned about the potential pollution.”

The owners of vessels no longer in service can hire a private company to drain all of the oil aboard or cover the cost of its removal by the Coast Guard.

The good news is that marine inspectors and responders in the Pacific Northwest receive overwhelming support from local mariners and residents.

“It’s a really environmentally-friendly area,” said Debrum. “Everything gets a really big interest here.”